Breadlines

One Woman's Experience in 1931

| ← Relevant Chapter | Story Index | Next Chapter → |

Publication Date: September 6, 2024

Dana LeFurat

In March of 1931, Dana LeFurat published an article in the Greensboro, NC News and Record about her experience at a Salvation Army breadline in downtown Greensboro. I’ve not been able to find Dana in the historical records, so I’m not sure if she was a real person, if the piece was written under a pen name, or if the entire thing is fiction.

I do know, however, that “A Lady in the Breadline: If You are Unemployed, and Hungry Enough to Swallow Your Pride Before Gulping Down Food, These Handouts Really are not so Bad” provides a deeply nuanced look at what life was like for the millions of Americans who were suddenly unemployed, underemployed, financially ruined and emotionally battered during the Great Depression. 1

Not in their own circles

“The breadline! I had read – I had heard of – I had seen – the breadline. In fact, the first time I saw that line of men standing so patiently – not, so stolidly, stoically – in the cold, I was seated in the back seat of a limousine. I shivered and looked away. Then I laughed, as I leaned back against the soft cushions of my friend’s car – and was accused of being heartless. But my laugh had not been from heartlessness. I had laughed as we often do when we have missed a catastrophe by a hair’s breadth.

“That was in the fall. In my pocketbook was all of my wealth – just 65 cents. The shoes on my feet were light pumps with lizard skin vamps – and not very suitable for winter, which was just around the corner. My coat was light in weight, too light to ward off the coming winter winds. I owed one month’s rent. My grocery bill was overdue. And so you see though I looked upon that breadline from the tonneau seat of a limousine, I was not much better off in the world’s goods than the men who were standing in it. But I was still not much alarmed. I was in line for a position – an executive position that would pay me not less than a hundred dollars a week. A few weeks’ salary and I would be able to clear my debts, buy winter shoes and a winter coat.”

But the hoped for position never materialized. Nor did the next, nor the one after that. In fact, despite Dana’s qualifications, experience and effort, she was unable to secure any kind of work anywhere.

“I had succeeded in paying electric, light and telephone bills and kept in small spending money by the pawning of what few valuables I had. Then came the day when there was nothing left to sell. Winter had arrived, and an old fur coat discarded several years before was keeping the cold away – but did not cover my pride. It was shaggy, hopelessly beyond repair—that is the home repair I could give it. The light pumps had not been replaced by winter shoes – but fortunately the winter had been free of snow. My credit had been cut off at the grocery store, and it was no shame to the merchant, who had carried me on his books longer than his judgement should have prompted him.”

Then one day, all the groceries had been eaten, Dana’s cupboards were bare.

She could have turned to friends – many of whom were still wealthy despite the economic downturn, but she didn’t, writing:

“One can speak of a $50,000 loss or bewail the fact that one’s income has dwindled to a mere $40,000, but you cannot tell your friends who have money that you have less than 50 cents between you and the breadline without seeming to actually hold out the cup for charity. Of course everyone knew that things were bad with me, but they were too engrossed with their own troubles and too far from actual want to be able to visualize anyone really having so little. That condition to them existed only in cases which charity organizations looked after – not in their own circle.”

Ditto for family, but for different reasons.

“Of course, if I had asked, they might have helped – but I am not sure. I have heard people speak of acquaintances, relatives who had hit the toboggan slide of bad luck in the tone that the victim was guilty of laziness – not really trying to find work. In the same breath that they spoke of the distress of the unemployed they criticized Friend Bill or Brother John for lack of ambition. Familiarity breeds contempt even for the legitimacy of poverty.”

Instead, as one day without food turned into two and then three, Dana told herself she was just dieting, not starving.

“Then I thought of the breadline. Could a woman of my class go to the breadline? No, the thought was too much for me. I lay in bed, too weak to be up, hoping that I would die, but death does not come so easily. Again the thought of the breadline. But just where were they located? Oh yes, one always asks information for anything of that sort. My fingers dial 411. “Information, can you tell me where there is a breadline?”

The woman who answered Dana’s call seemed surprised, maybe even shocked, by the question from someone with such a “cultured” voice, but eventually referred Dana to the local police station. And, after another awkward conversation, Dana got the information she was looking for, Ned Hutton’s breadline on Tenth Avenue and 35th Street was the best choice for women.

“And as I click the receiver back into its place I resolved that that was the end of the “breadline” idea. Why had I created such a stir by asking for something which surely was a common demand these days?”

Sometime later, Dana said a friend dropped by, and, seeing how weak she looked, assumed Dana was not feeling well. Soon after, a delivery boy arrived with a package containing a dozen oranges and grapefruit.

“Oranges, grapefruit – when I wanted roast beef, bread! But the next moment I was grateful when I thought she might have sent flowers. And, too, I had heard of a citrus fruit diet. You lived for five days on nothing but the juice of oranges and grapefruit. So I began my enforced diet, and found that it was refreshing – satisfying in a way.”

With some energy and a new sense of hope, Dana’s mind returned to the breadline.

“I laughed now over my telephone experience of the breadline. I had food for two or three days and anything might happen in that time. And now that the breadline was not imperative, I thought of it with less fear. Why not see what it was like? It would be an experience – take is as experience, I reasoned. After all, if one cannot afford the theatre as an amusement, one can afford Life. That was all the theatre was, seeing other people’s experiences, trials and triumphs from a comfortable seat. Why not take a look at Life on the world’s stage and play a leading lady part? Why die, when there were things to see – emotions to experience?”

The next day was Sunday, and, thinking she was less likely to run across any of her friends – especially if she left at 7 a.m. – Dana decided to walk to Ned Horton’s breadline and experience it for herself.

And she made sure to dress the part.

“What a comfort to dress for the breadline! The worse one looked, the more appropriate the costume. The shaggy fur coat with the rents which would not stay sewed was now welcomed as part of my attire. Gloves? I did not need to wear my only decent pair which I had been saving so carefully since they were given to me at Christmas. Nails? No need to manicure and use the liquid enamel which was getting low. A safety pin held the collar of my coat where the cord had worn in two. No need to brush and try to make my shabby hat look jaunty, Shoes? Gee, I could wear a pair that I had discarded last spring, they were more comfortable than the lizard skin pumps even thought they were run down at the heels and the tows were scuffed. No need to worry that my hair was shaggy around the neckline. And no use wasting makeup. Gee, it was comfortable to be a hobo!”

Despite the early hour, Dana saw several children on the street, each carrying a loaf of bread, a can of milk and a small package – food they’d gotten from one of the many relief stations for the families of the unemployed established by grocery giant, A & P Tea Company.

“Another block and I saw a group of men lined before a building which had once been a church. I had reached my destination – but to my dismay I did not see a single woman. I half turned away, when a man with a friendly smile standing in the doorway caught my eye and I gained courage to ask, ‘Have you a department for women?’

“I could not back out now, for he put a friendly arm around my shoulders and drew me in. The men crowded at the door made room for me to pass. I was just in time – in fact, the doors of the dining room did not open officially until 8 o’clock.”

As she took her seat at one of the whitewashed wooden tables, Dana found herself thinking of bacon and eggs, then reminded herself she was there for the experience, not for the food.

“I probably would not eat only pretend. But my stomach kept up the wincing for something solid – at least not orange juice.”

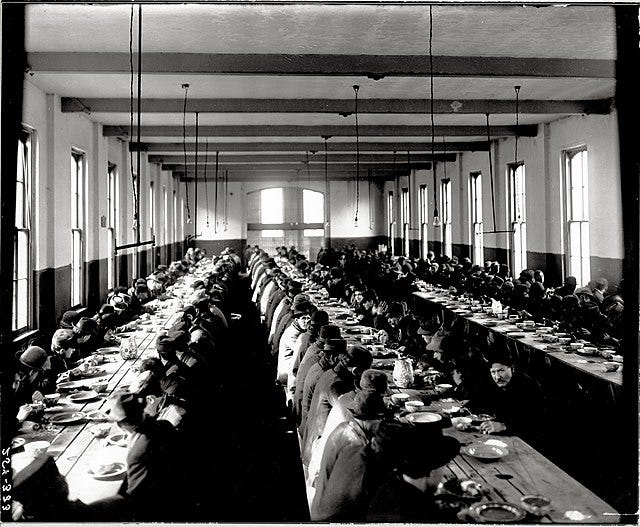

When the appointed time arrived, the main doors were opened, and the men came filing in.

“I was surprised to see them walk so orderly to their places, almost as if they had been drilled. They seated themselves quietly – in fact, there was not even a murmur of voices! There was no public prayer before the meal, thank goodness! The feeding of those hungry men was the biggest prayer that could be uttered.”

Waiters began serving almost immediately, setting before each man and woman a bowl-sized serving of oatmeal and a cup of steaming coffee.

“When I saw the food – I realized I was in the breadline. I was seated at a charity board – with the rest of the failures of the country. I squared my shoulders – no I was here for the experience (there were those oranges and grapefruit.)

“Physically I pulled up my pride; head up, shoulders squared – my hands pulled my hat at a more jaunty angle. No use – mentally I sagged. And I found myself mumbling a shamefaced, incoherent “thank you” to the waiter.”

Although she was thankful for the food – the first she’d had for several days – Dana was overcome with humility and something else, shame.

“I felt a shifty feeling coming over me. There is no doubt charity is demoralizing. I could feel it seeping through my soul and oozing out of my body. I was down – out! I had forfeited my right to the society of the worth-while people! Derelict, vagabond bum!”

It was then that Dana took note of her companions.

“There must have been 500 men in that room eating in one room – and silence. Not ominous – just dead! Set faces – what were they thinking? That was it – they were thinking. Thoughts of shame, thoughts of failure, thought of despondency.

“They probably had not been here before and expected to come again, could see no hope of ever again rising themselves to economic independence. They were not bums, hobos. Most of them wore white collars, cleanly shaven faces, brushed clothes. Men past the prime of life, not old, no – just growing old. Only here and there was a very old man, and rarer still a young man.”

Her eyes were drawn to one young man. Unlike the others, he didn’t appear to be depressed or ashamed. Instead, his look was that of a man determined to weather the storm as best he could and any way he could.

And, most remarkably, the man appeared to be at peace.

“His manner was that of a man seated at his own table where food was being served from a well filled larder. A strong face and a strong, healthy-looking body.”

Dana guessed him to be a mechanic, someone who had earned good wages not so long ago, and expected to earn them soon again.

And that, Dana realized, was the difference.

“He was not in the breadline because of his failing. He was ready to work; fit morally and physically for what life had trained men – that is, to earn his living by honest work. But there was no work, not through his fault. No, the fault belonged somewhere higher up. Somehow the system had gone wrong. He was not bitter, critical – he was no red. When the powers in command had gotten the country out of the mess, he would be ready. In the meantime he was keeping fit by taking what belonged to him – not charity.”

The man’s mind shift was nothing less than an epiphany for Dana, who just moments before had felt hopeless and demoralized at having to accept the oatmeal and coffee offered at the breadline.

Like the man, she need not be defined by her present circumstances. She could continue to hold her head up, seek out goodness and light wherever she could find it, and plan for a better future – a future where she would, once again, be gainfully employed in a job she enjoyed and was good at, and one that met her financial needs.

She would survive these hard times without falling apart or second-guessing her worth, and she would do it without shame.

As Dana left the dining room, the attendant thanked her for coming and said he hoped to see her again.

“I said I would be back,” Dana wrote. And she did.

A Lifeline for Millions

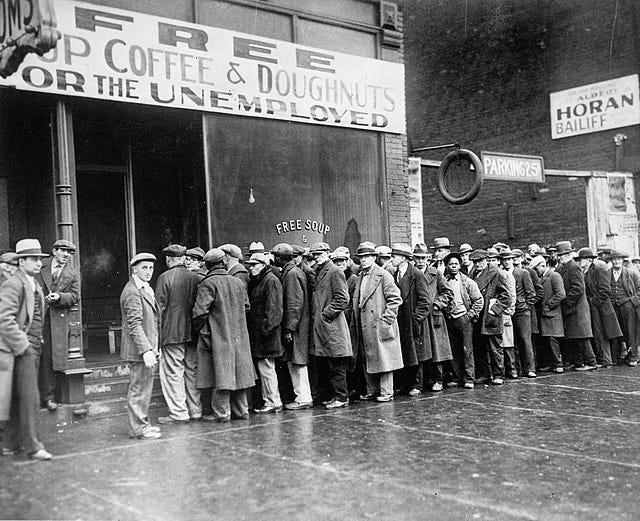

During the Great Depression, breadlines became a common sight across the United States as millions of people relied on charity for their basic needs. While it's difficult to pinpoint an exact number of people who used breadlines, estimates suggest that at the height of the depression in the early 1930s, as many as 12 to 15 million Americans were unemployed and many of them, along with their families, depended on some form of charity for food.

In major cities, breadlines often stretched for blocks, serving thousands of people daily. For example, New York City alone had scores of soup kitchens and breadlines run by organizations like the Salvation Army, churches, and local relief agencies. Nationally, charitable organizations, local governments, and businesses set up thousands of similar relief stations to help feed the unemployed.

The severity of the crisis peaked between 1932 and 1933, when unemployment reached about 25 percent of the workforce. Many of these individuals and families turned to breadlines, soup kitchens, and relief stations like A&P’s to survive.

| ← Relevant Chapter | Story Index | Next Chapter → |

Copyright 2024 Lori Olson White

Chapter Endnotes

Dana LeFurat, “A Lady in the Breadline: If You are Unemployed, and Hungry Enough to Swallow Your Pride Before Gulping Down Food, These Handouts Really are not so Bad”, News and Record, Greensboro, NC, March 15, 1931, P. 3B.

Pulled me in and showed me what breadlines meant then.