Margin Notes: Death at 816 Whitcomb Road

An inside look at my approach and processes, some of the challenges faced, and my own theory of what might have happened

| Margin Notes| Start from the Beginning|

Release date: August 5, 2025

Hi, and welcome to the Margin Notes on Death at 816 Whitcomb Road, a special feature for paid subscribers here at The Lost & Found Story Box. If that’s you, thanks so much for your support! Your generosity makes it possible for me to do what I do.

The Arturo Fulvi family’s story was my first true crime lost & found story, and today I’ll be sharing a little more about how I approached it and some of the challenges I faced in putting it together. I’ll also be sharing some of the information about the deaths and circumstances around them that maybe wasn’t readily available or known nearly a century ago when this tragedy took place.

And finally, I’ll offer some of my own questions I have about what happened that cold January night when Arturo Fulvia and five of his six children died.

So, let’s jump in and see what we find!

A story with an intentionally short shelf life

Unlike a lot of lost & found stories I share here, the story of the deaths of six members of Cleveland’s Fulvi family was found fairly complete and in a newspaper from Brownsville, TX, of all places! Apparently the story had been picked up by the Central Press Association, a Cleveland-based new syndicate and sent far and wide: I later found the same piece in newspapers all across the US.

This was the same piece that asked readers to help solve the case, something I found interesting, especially after doing the research and coming to my own conclusions about the veracity of the coroner’s conclusion, the family history and everything else that seemed a little off. Perhaps the Central Press owners had some ideas of their own, too. Oh, and the earliest publication of the piece I found was February 7, a week after the case was closed. The latest was published in October! Again, curious.

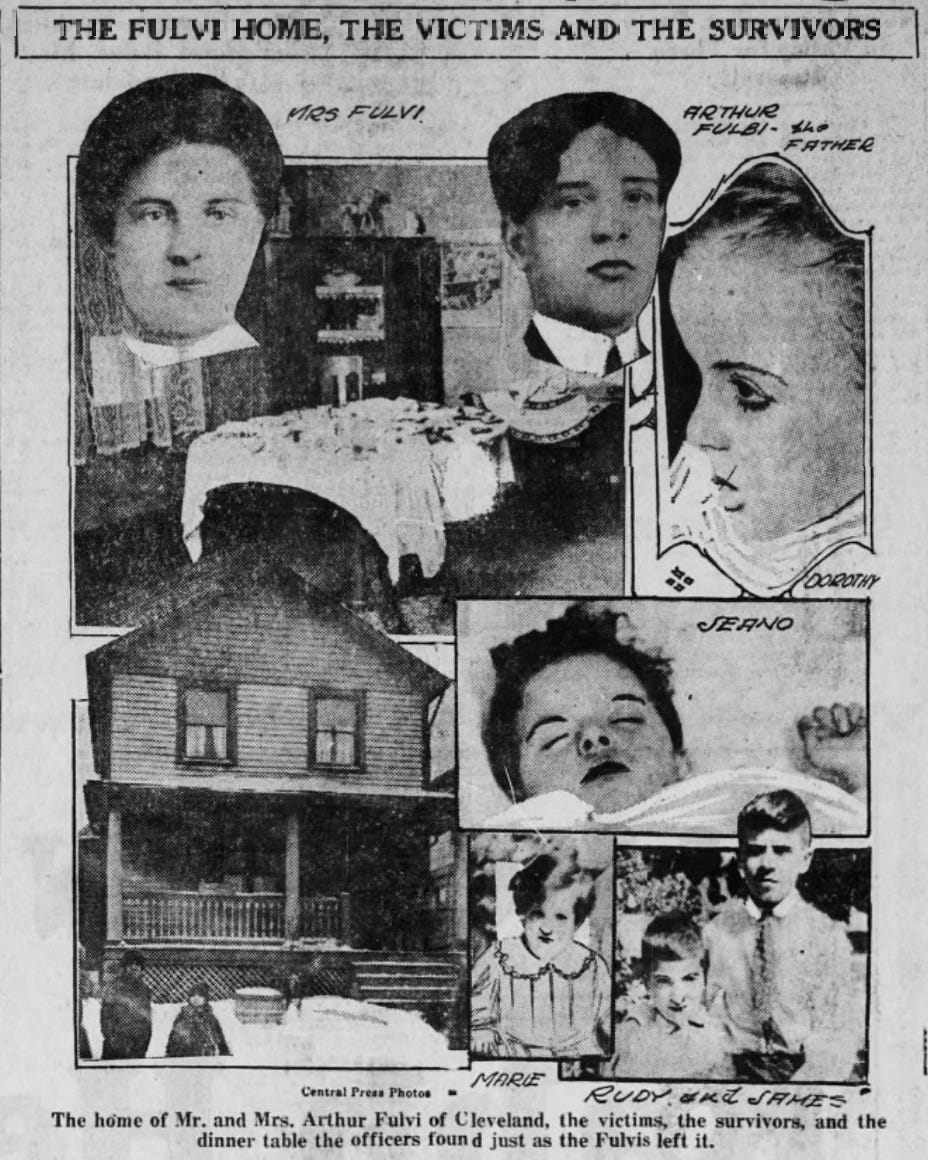

Likely because it was a Cleveland-based service, the syndicated piece was also the only one which included photos of everyone in the family except Victor, as well as photos of the exterior and interior of the house.

A note on names. The records and documents go back and forth on names and spellings especially for the father, Arturo, and three-year-old Eugene, but also for extended family members. Eugene, for example, was referred to as Eugene, Jeano, Gino and Jingo. I went with Arturo and Gino just to be consistent.

Another interesting thing about this story was just how short the window of official inquiry was. The bodies were discovered late afternoon of January 29 and the coroner’s report was completed just 48 hour later on the evening of January 31. Talk about a quick turnaround.

Even the newspapers were quick to bury the story. The first reports came out in the evening papers on the 29th, and the final local reporting — coverage of the funerals — was on February 2.

The only original followup reporting on the story was that Elvira had been released from hospital and was moving to Altoona to live with her sister, Anna.

Then there’s the coroner’s conclusion: Arturo, James, Rueben, Dorothy, Mary and Gino had probably died of carbon monoxide poisoning, even though only two autopsies had been conducted, liquid poison was found in the system of one of the victims, and some of the forensic tests were still being completed.

And even Gino had what doctors described as chemical burns on his lips and tongue, and no autopsy on his body was not done.

And even though Elvira, Gino and the family’s pets had all initially survived despite reportedly being in the same house for the same amount of time, and breathing the same deadly fumes as the first five victims.

I don’t know about you, but those seem like some mighty big red flags to me.

Looking for clues

In addition to reviewing all the newspaper articles about the case, I researched crime records for the Greater Cleveland Area, Italian immigrant culture and traditions, prohibition and bootlegging in Cleveland and the state of forensic science at the time. And I spent hours learning more about a wide variety of natural and manufactured poisons, their symptoms and timelines, availability and examples of deaths in which they were used.

Although most of my research was done the old fashioned way — books, magazines, newspapers, journals, reports and other archives material, I did engage with both Claude.ai and ChatGPT to cross-reference physical evidence with known symptoms of different poisons available in 1925-1926 in an effort to explain what might have happened. (My best guess is at the end of this Margin Note, btw).

I also created dozens of tables and timelines in my attempt to include all the information and create some sort of cohesive, logical and likely scenario.

I can see how people become obsessed with true crime stories! Once I started hypothesizing, it was ridiculous where my mind went!

As always, If you have any specific questions on my process or see something I missed or didn’t get right, please drop me a note. Also, if you’ve come up with a theory, share that, as well. Maybe we can crowd source a better answer than the 1926 one.

Another look at the coroner and the system

Newspaper accounts of the investigation into the Fulvi deaths as well as forensic science in use at the time suggest Cleveland’s coroner was capable of running a limited number of tests on the Fulvi blood and tissue samples to determine the presence of poison, including from carbon monoxide gas, but also poison that would be found in liquids like alcohol.

Yet, an article published in December 1925, just a month prior to the Fulvi case, seems to suggest even those tests were rarely run.

That article noted that 379 people had died of “poison booze” in Cuyahoga County in the previous four-year period, yet not one case had been brought to prosecutors.

The reason?

The coroner — at least according to county law enforcement.

“If [the coroner] should ever tell us that poison was found in the stomach of a dead man who died from liquor, we’d have something to work with. But he never does.”

In response, the coroner blamed time.

“Time elapsed between the death and the taking possession of the body by police. Time elapsed between the time the body arrives at the morgue and the stomach is removed by me. Time elapsed between the time the stomach is removed and the chemist analyzes the contents. In the meantime, what happens? If there is any poison in the stomach…it has disappeared by natural, physical means. I cannot report that there might have been poison when I actually didn’t find any.” 1

Mm.

The coroner put the time of death for Arturo and his four older children at between 3 a.m. and 4 a.m. Friday morning, a good 12 hours before the bodies were discovered and brought to the morgue. And the autopsies on just two of those bodies — Arturo and Rueben — weren’t completed until sometime Saturday evening, a full 24-hours later, and some 36 hours after death.

How much time was enough time for poison to reliably “disappear” from a victim’s body? Thirty-six hours?

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Lost & Found Story Box to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.