The Epic Canoe Journey of George W. Gardner: PART 6

What happens when a riverboat captain plays a practical joke

To get the most enjoyment out of this serialized story, please start at the beginning.

Release Date: May 6, 2025

If you were here, you’d be there

With the excitement of the Falls of the Ohio safely behind them, George and William set their sights on the entrance to the mighty Mississippi River near Cairo, IL. Although just over 200 miles distant as the crow flies, the meandering Ohio River meant the journey would expand to nearly 400 miles, at least according to guidebooks of the day.

But as the two Ohio canoers found out, guidebooks weren't always accurate.

We had pulled out of Louisville at 2 o’clock, made the dash over the falls of the Ohio, and having caught some dampness in the operation, concluded to go into camp under a roof, and the town of Bridgeport, IN, twelve miles below Louisville, was determined on. Our guidebook informed us that Bridgeport was a town of 200 inhabitants, where boat building was carried on quite extensively.

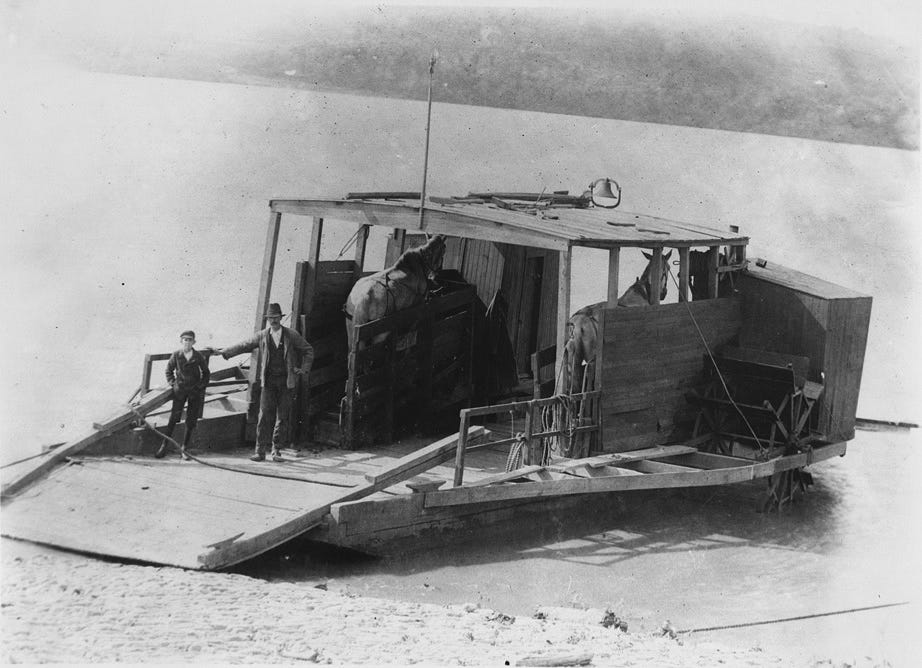

We were skirting along the Kentucky shore, with an eye windward to discover this enterprising town, when a nondescript craft, a cross between a Chinese junk and a threshing machine, hove in sight, near the other shore; a ferry-boat proprieties by two horses – that is to say, an assortment of hone and horsehide, tramping in a circle on the main deck, and thus turning two spavined wheels. The crew consisted of father and son, both fitted to their vocation and surroundings.

Having sized up the craft, we hailed the master, “Ship ahoy, stranger, where’s Bridgeport?”

“If you were here, you would be there.” Came the somewhat paradoxical answer.

We got there.

“Can we find a place here to put up overnight?” was our next query, as we clambered on deck.

The modern Sharon eyed us closely for a moment, sized up our brown physiognomies and our butternut togs, and then knocked us over with,” Well, I don’t know about that – what be you anyway – chicken thieves?”

Slipping out of our uniforms, our shore clothes underneath, we had no difficulty in satisfying his scruples, and Mr. Ned Smith, the ferry man, housed is in his snug little cottage, half a mile back from the landing, gave us a supper and a breakfast, and in company with the entire family, escorted us to the canoes in the morning and waved us bon jour.

Our host’s family consisted of himself, his wife, four strapping sons, a buxom daughter and a pretty visiting niece from Canada. The most enjoyable feature of a pleasant evening in this godly company was the host’s account of himself.

An Irish immigrant, married soon after arriving, drifted to New Orleans, got scared at the sin and wickedness of the city, declared his conviction that the thin crust of diet upon which the city was built would one day break up, started north on a steamboat, froze in at Bridgeport, disembarked (this was in 1850), found the whiskey good, cheap and plentiful, and stayed.

I would like, had I time, to pay tribute to this good natured, jolly, happy-go-lucky son of the old sod for his hospitality, but may only say that the memory of our sojourn under his roof is an abiding one, even if her did inject bitterness into our souls by suggesting chicken thievery.

Faith in our guidebook was rudely shaken by Smith’s assertion that the town never had over fifty inhabitants, he never knew of a boat being built there, and as to Blakesville, six miles below, as the guidebook had it, he never heard of the place. 1

River guidebooks of the day were often more concerned about the features of the river than the small towns and villages along the way, many of which had only informal landings.

Neither Bridgeport nor Blakesville appeared in The Western Pilot, for example. In fact, the popular guide featured just four towns within 35 miles downriver of Louisville: Shippingport, KY, “a small town, fast going to decay”; Portland, KY and New Albany, IN, on the left and right banks of the river respectively; and Brandenbugh, KY, where a “considerable business [was] done… in tobacco, pork, &c. for the Southern market”.

But, the guide also made mention of “a frame house on the left” near the mouth of Knob Creek, 10 miles beyond Louisville; a “house at the mouth of a run” a mile and a quarter past where Salt River entered the Ohio ; and the “Tobacco landing” just beyond Otter Creek and three miles past the Salt — any of which may have been the location of Ned Smith’s home. 2

Another popular river guide of the day, Conclin’s New River Guide, included much of the same information, however, added a few more details.

Shippingport was described as “a small and rather dilapidated village containing one fine mill, four small stores and groceries, and a population of about one hundred and fifty”.

And Portland offered “a line of omnibuses run from it to Louisville every few moments in the day,” and was “connected with New Albany by a ferryboat, which plies almost constantly.” Perhaps this was the ferry manned by Ned Smith.

Conclin’s also included a small village named West Point, KY, located “just below the mouth of the Salt River”, so roughly 20 miles south of Louisville. The village included four stores, but also a boatyard which was “commencing an extensive business”. 3

Please hit the ❤️ button at the bottom of the page to help this story reach more readers. And if you’re not already a subscriber, I’d love to have you join me. Thanks!

A game of hunt the canoe

Like Bridgeport and Blakesville, Bay City wasn’t named in the two main river guides of the day. However, 330 river miles south of Louisville, the Cumberland River entered the Ohio near Smithland, KY, creating an unusually wide expanse of the river.

George and William came to this “miniature lake” late in the afternoon, some six days after their passage over the falls. It had been a quiet day with no craft of any kind to keep the canoers entertained.

Then suddenly everything changed with the appearance of the side-wheeler Henry T Dexter at the other end of the expanse.

The skipper was fully half a mile in the lead and the Dexter that much further downstream and hugging the opposite bank, but in a few short moments she swung gracefully into the stream heading directly for the skipper; and then began a series of dodging.

The Steamboat bent upon running the canoe down, and the canoe animated in a very apparent disinclination to be swamped in that way. The guileless scribe looked on, wondering by what freak of nature the channel had been made so erratic, and what force was keeping the skipper directly in that steamboat's path. He found out.

On came the Steamboat well to the starboard, but now she heads directly for the scribe. Laziness and mediation of nature's mysteries vanished, and the paddles were plied vigorously.

In vain.

The nose of that puffing monster remained directly in front, a foreshortened leviathan. That weary perspiring scribe “tumbled to the racket” only when that Steamboat was within 100 feet of him, dropped his paddle, and shouted his benediction to the pilot, whose face broadened into a benevolent smile as he peered forth from his eyrie between the smokestacks. 4

So much for a lazy afternoon of paddling.

George and William had unwittingly become participants in a long-standing tradition of shenanigans and practical jokes carried out by riverboat captains and others who regularly plied the waters of the Ohio and Mississippi rivers. Whether to fight off boredom, establish a pecking order or assert authority through intimidation, these mostly harmless activities were both common and legendary, and ran the gamut from expelling huge black clouds of smoke when passing a lesser vessel to feigning disinterest to onlookers while maneuvering through dangerous waters.

It’s also possible Captain Luty had heard about George and William through local newspapers as well as river’s unique communication system. Word of the gentlemen from Cleveland and their pleasure cruise down the Ohio and Mississippi would surely have been passed from riverman to riverman at landings, while on shore and even in passing.

It’s not impossible that Captain Luty’s game of “hunt the canoe” was just his way of making sure George and William had a good story to tell when they got back home.

The spook of an unhappy canoer

Later that evening, George and William stopped for the night in Paducah, KY, and, given the adventure they’d had, the two decided to forgo camping and stay instead at the Richmond House. One of the finest hotels on the Ohio River, the stately establishment was a popular spot with rivermen, as well as traveling dignitaries, gamblers and bigwigs.

And for good reason.

In addition to its 54 state-of-the-art rooms, the Richmond House also boasted an in-house barber, a merchant tailor, a full-service shoe shop and a barkeeper who ran a mail order whiskey business and lottery on the side.

And, if that wasn’t enough, there was reportedly also a betting house run out of the lobby which saw up to $8,000 change hands each day.5

Sometime during their stay at the Richmond, William took a moment to pen the following “billet doux” to William Luty, the captain of the Henry T Dexter.

Paducah KY December 1883.

William: Your bowels of compassion must be shrunken, even to the dimensions of a mustard gem; in fact, if you have no more bowls than you have compassion, I wonder what stowage you can find for feed. Yet you look very like a party who feeds well; but, my friend, do you not stand in fear of a possible ghost – the spook of an unhappy canoer – that may come to you in the dead watches of the night, to confront you with your inhumane chase of two innocent and guileless strangers over the broad expanse and waste water near Bay City today?

How could you do it.

We enjoyed it when we “got on to your racket”, but it was hot for a brief season.

If you ever find yourself in our neighborhood, find us, and we will recall the incident that relieved a long day of paddling, W. H. Eckman 6

The latent courage to open a letter

William likely sent the letter to Captain Luty in care of one of the designated post offices that had been established at major landing points along the Ohio River for just that purpose. Upon landing, captains would send a crew member to the post office, and retrieve any mail that had accumulated.

Several weeks later, Captain Luty did just that, at least according to the Evansville (IL) Journal:

Readers of the Journal will remember a paragraph a few Sundays ago, descriptive of two canoes making their trip with their occupants to New Orleans from Cleveland and Cincinnati. The boys started here (in Evansville) Sunday morning, paddled to Bay City, where they met the Dexter.

Bill Luty was at the wheel, and in a spirit of fun headed the Dexter for one of the canoes. The boys had been paddling about the upper lakes where small crafts are in the habit of getting out of the way of steamers instead of steamers getting out of the way of small craft. When the occupant of the canoe saw Dexter heading for him, he was floating leisurely in the sunlight, but, quickly panicky, grabbed his paddle and paddled for dear life to get out of the way.

It pleased Bill to see him work, and having plenty of river, he headed her for the other canoe, whose occupant also took a big scare and paddled frantically out of the way.

Bill kept it up until the boys took in the situation and realized that he was having some fun at their expense, put up their paddles, and went to mopping the sweat from their brows with their bandanas.

On arrival at Paducah, going down, somebody handed Bill a letter with the card of the Richmond House on it, and directed to him. Bill had a guilty conscience, and is naturally, as Mooney expresses it, “a suspicious character”, and was afraid to open it.

After a trip or two he got over his scare, and by the constant importunities of Captain Damron, King Cobbs and the other boys on the boat, took courage, opened the letter…a little late, it is true, but none the worse for the age. 6

It’s not known if Captain Luty ever took William up on his offer, but the inclusion of the incident in George’s retelling of the tale would indicate encountering the Henry T Dexter was a highlight of the journey for both men, and a one which was likely told — and elaborated on — many times over the years.

As should be any good river story.

Copyright 2025 Lori Olson White

Have you read the incredible true story of Aimee Henry and Mary Martha Parker? Call Me a Bastard is my longest serialized story to-date, and the one that started it all here on the Lost & Found Story Box. Check out the story from the beginning.

And in case you missed it, here’s a link to my most popular short series to-date, The Show Must Go On: A Circus Story of Motherhood and Resilience. I hope you’ll agree that Blanche Ponche’s story is one worth retelling!

Please hit the ❤️ button at the bottom of the page to help this story reach more readers. And if you’re not already a subscriber, I’d love to have you join me. Thanks!

The Lost & Found Story Box is reader-supported. When you buy through links on our site, we may earn an affiliate commission.

End Notes

1 “The Mayor in a Canoe: His Adventures. Between Porkopolis and the Crescent City in Midwinter”, The Cleveland Leader, Cleveland, OH, January 26, 1890, P. 10.

2 Samuel Cummings, “The Western Pilot; Containing Charts of the Ohio River and over the Mississippi River, from the Mouth of the Missouri to the Gulf of Mexico; accompanied with Directions for Navigating the Same and a Gazetteer; or Description of the Towns on their Banks, Tributary Streams, etc., also a Variety of Matter Interesting to Travelers and all Concerned in the Navigation of those Rivers; With a Table of Distances from Town to Town on all the Above Rivers.” Published by George Conclin, Cincinnati, OH 1837.

3 George Conclin, “Conclin’s New River Guide, or a Gazetteer of All the Towns on the Western Waters”, H. S. & J. Applegate, Cincinnati, OH, 1849.

4 “The Mayor in a Canoe: His Adventures. Between Porkopolis and the Crescent City in Midwinter”, The Cleveland Leader, Cleveland, OH, January 26, 1890, P. 10.

5 “From History to Here” by J. T. Crawford, Paducah Life Magazine, January/February 2020, P. 11-12.

6 “The Mayor in a Canoe: His Adventures. Between Porkopolis and the Crescent City in Midwinter”, The Cleveland Leader, Cleveland, OH, January 26, 1890, P. 10.

7 “Local Notes”, The Evansville Journal, Evansville, IL, January 8, 1884, P. 3.

So much to discuss here. But why in all creation would Ned associate a butternut suit with chicken thievery???

Geez, a fine sense of fun you have there, buddy!