The Incorrigible John George: Part 1

Part 1: Who was John George and how did he wind up in so much trouble?

I came across this lost and found story while conducting research on an ancestor of mine who moved from Wisconsin to California in 1906, arriving in San Francisco four days before the devastating Earthquake, and then falling off the face of the earth for three decades. Another great story for another time!

This story was published January 30,1926 under the headline, “Bootlegger, 84, Must Serve Despite Age”, and like most good teasers, this one was short and sweet:

Despite his 84 years, John George, Confederate veteran and great grandfather, must leave his young wife and 3-year-old son to serve a six-month sentence for violation of the prohibition laws, the Alabama Supreme Court ruled.

There’s a lot in there, right!

But I had no idea what I’d find, or how relative it would be to the world we live in today.

Welcome to Part 1 of another great lost and found story, The Incorrigible John George!

If you enjoy this story, I’d really appreciate it if you’s click the “like” button at the bottom of this page. It’s a small click that makes a big difference—it helps others discover The Lost & Found Story Box and keeps our community growing. Thanks for your support!

Release Date: January 7, 2025

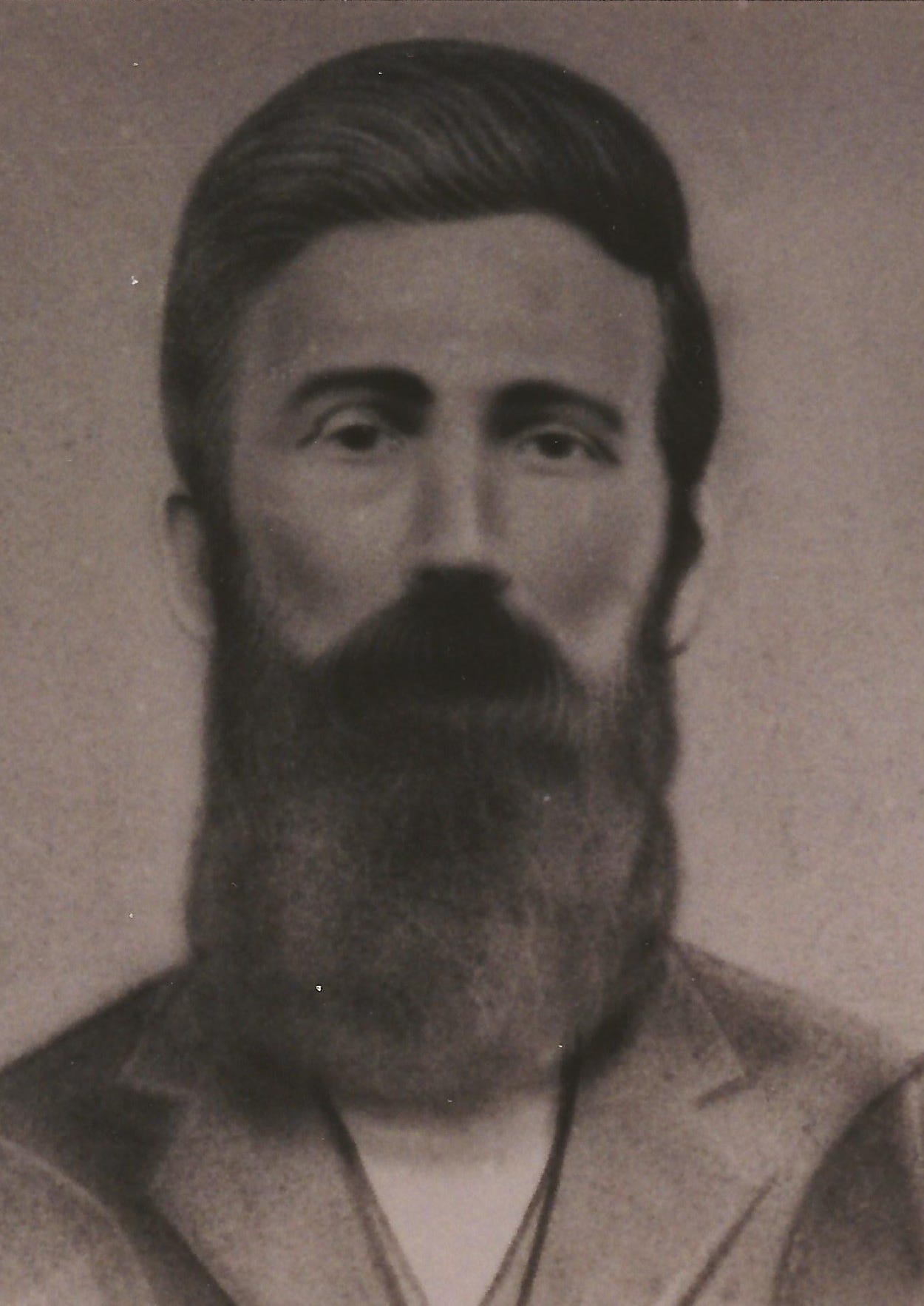

A lifetime of troubles

John Mathias George was born three days after Christmas in 1842, the sixth of nine children of Elias George and his wife, Nancy White George. John’s father, Elias, was a farmer and veteran of the Creek Indian Wars of 1814, having served in the M Infantry under Captain James Tait January 28, 1814 to May 10, 1814. 1

He was also a slaveholder, owning 31 slaves at the time of the 1840 census, more than all of his neighbors combined. 2

By early 1862, all four of Elias’s sons as well as both of his sons-in-law had answered the call of the Confederate Army, including 19-year-old John. On May 1, 1862, he’d enlisted as a private in Company H of the Alabama 40th Infantry under the command of General Joseph E. Johnston. 3

What happened next is up for debate, but what is known is that sometime in October of 1864, John was back in Hale County and working the land with his father.

Five years later, 28-year-old John married a local girl named Julie Ann Johnston. She was just 14, and would be a mother of two before her 17th birthday. By 18 she would be dead, and John would be a widowed father to two small children.

In January of 1875, John married his second wife, Mary Susan Ross, and the two settled into what would be a nearly fifty-year marriage, though one that was not without its challenges. Legal and otherwise.

The first took place on February 7, 1888, when 46-year-old John had a fatal encounter with Benjamin Boggs, a local Confederate veteran but also convicted murderer who’d spent time in the State Penitentiary.

According to John, he and Benjamin had a long-standing beef of unknown origins. As both were known moonshiners, that may have had something to do with it, however, it could also have been just a business deal gone wrong. The previous year, John had sold Benjamin an old wagon on credit, and Benjamin had allegedly reneged on the payment. And, although John was the one wronged, it was, he claimed, Benjamin who’d held the grudge.

In the month leading up to that fateful February day, in fact, Benjamin’s grudge had festered into overt threats of violence, and he’d gone about town announcing his intent to kill John when next they met.

And John had taken the threats seriously. So seriously, in fact, that he’d stayed home for nearly a month, “fearing even to haul his cotton to a gin several miles from his house to have it ginned”. Eventually, however, the owner of the gin had sent word, warning John that if he didn’t get his cotton in, it wouldn’t get processed, so John had loaded up his wagon and taken his cotton to the gin.

On his way home, he’d encountered Benjamin.

Again according to John’s testimony, when the two passed each other on the road, Benjamin threatened to kill him, then grabbed a heavy iron wedge from his wagon, and made a move in John’s direction.

Before Benjamin could act, John took aim and shot him in the face with a round of buckshot. Benjamin died on the spot. Then John and his brother-in-law, John Colbourn, got back into the wagon, and went home.

After sending word to Benjamin’s family as to where they could find his bullet-ridden body, John, his brother-in-law and the local minister went into town, where John surrendered to the local sheriff. 4

Almost immediately, folks started taking sides, with some calling the killing outright murder and others saying it was delf-defense. Attorneys were hired, a Grand Jury was called and one of the most high-profile, complex and drawn-out court cases to come through the Hale County Court in quite some time was underway.

“The preliminary trial of the case of the State vs. John George for the killing of B.F. Boggs on the 7th of February last which was begun before Justices J. T. Smith and E. T. Pasteur in Greensboro on Monday, March 7, was continued throughout the entire week. One night session was also held. The court adjourned late on last Saturday evening until today (Thursday), when a fresh start will be taken. Already the Prothonotary has taken 375 pages of deposition on paper the size of legal cap, and the end is not yet. We refrain from any comment upon the evidence given. The case is likely to be in the courts for several years.” 5

On April 22, 1890, two years after the shooting had taken place, the jury returned a verdict of not guilty, and John walked away a free man. A total of seven attorneys had been engaged in the lengthy court battle, and, according to papers of the day, the courthouse was “thronged” with bystanders when the verdict came down. 6

None the worse for the wear, John returned to farming and to bootlegging.

Seventeen years later, in December of 1907, trouble found John once more when he was the target of an assassination attempt by Hale County brothers Jim and John Langford, ages 15 and 13 respectively. In what was described as a roadside ambush attack, one bullet struck John, and the “balance of the buckshot from the other gun” hit his Black driver, Coleman Armstrong, in the thigh. Neither man was seriously hurt, and John could provide local law enforcement with “no reasons why the brothers should have shot him” 7

That may or may not have been the truth.

As had happened in 1888, the reason for John’s misfortune may have had something to do with his career as a moonshiner. Just a month earlier, the Alabama legislature had voted to prohibit the production and distribution of alcohol. With legal alcohol outlawed, the demand for liquor made and sold by men like John had immediately skyrocketed and competition among bootleggers for clients and sales territories had grown fierce.

It's not known if the Langford brothers were already involved in the illegal liquor trade in 1907 – they were, after all, just teenagers, however, by 1926, Jim was one of John’s biggest rivals in the business, and, like John, often a target of law enforcement attention. 8

With the passage of the 14th Amendment in January 1919 , Alabama and the rest of America entered what would be 13 years of nationwide prohibition. It would be both a blessing and a bane for bootleggers like John.

The blessing came with the increased demand for moonshine. The bane from the increased, and increasingly aggressive, enforcement of the laws against the manufacture, distribution, transport, sale and consumption of alcohol. In Alabama alone, nearly 18,000 people wold be arrested between 1919 and 1933 for violation of state and federal prohibition law. Of those, more than 10,000 would be brought to trial, including John.

On January 16, 1922, John’s wife of 47 years, Mary passed away.

Seven months and one day later, John married for a third time, and the marriage quickly became the talk of the town, and for good reason. The groom was a 79-year-old father, grandfather and great-grandfather. His new bride, Julia Ann Mitchell, was just 19.

She was also pregnant.

Julia gave birth to the first of the couple’s five children on March 13, 1923. And was well along in her second pregnancy two years later when John was arrested for allegedly violating the prohibition laws, leaving her alone to manage the family business.

As had happened before, John was able to game the system for several months before the case eventually went to trial. However, on January 20, 1926, Judge Samuel F. Hobbs of Alabama’s Fourth Judicial Circuit District handed down a guilty verdict, sentencing 84-year-old John to pay a $500 fine and court fees, and serve out a six-month confinement.

Whether his string of luck had finally run out or not was yet to be determined.

A chance encounter and friendly ear

On Wednesday, January 27, 1926, convicted moonshiner John George and a Hale County law enforcement officer took off on the nearly hundred-mile journey from Greensboro, AL to the Wegra coal mine located outside of Praco, AL. Enroute, they stopped for the night in Birmingham. While it’s unknown where John’s escort spent the night, John himself was the guest of the Jefferson County Jail, under the supervision of Warden Paulus E. Daniel.

At some point during his stay, John struck up a conversation with the jailor who, it appears, reached out to someone at the local paper to help amplify John’s version of the story.

By Friday evening, that story was the talk of the town. 11

In it, John was not a moonshiner, he was just an innocent bystander, a do-gooder, actually, who was in the wrong place at the wrong time. His wife’s cousin was the guilty party. He’d made the illegal hooch and left it with John in his absence, in case a friend-in-need stopped by.

As chance would have it, a needy friend did arrive, and an exchange was made. Later, that friend had gotten unruly around some temperance ladies. The police had gotten involved, and – to make a long story short – the friend had mistakenly identified John as the bootlegger.

“I am not guilty of the offense of which I am charged,” John explained. “I only delivered the message the cousin told me to. I have never made liquor, sold liquor and I don’t drink.”

Not only had John been erroneously charged and convicted, he’d also been denied his right to be tried by a jury of his peers.

A true travesty, but one deeply compounded by the fact that John was a veteran of the Confederacy, having served three years in Company H Fortieth Alabama Infantry Regiment, under General Joseph E. Johnson.

And he had the scar on his forehead from a Yankee bullet to prove it.

The very idea that a Confederate veteran, an octogenarian, a stoop-shouldered great-grandfather would be sentence to hard labor in a dank and dangerous convict coal mine was unimaginable and repugnant to a Southern man like Warden Daniel.

“There are only a few hundred [Confederate] veterans in the state,” he said. “Not one of them should have to spend their last days in jail unless it is for a far more serious crime, where there is no doubt of his guilt.” 12

It turns out Warden Daniel wasn’t the only one who felt that way.

Copyright 2024 Lori Olson White

Please hit the ❤️ button at the bottom of the page to help this story reach more readers. Thanks!

Be sure to check out Call Me a Bastard, a serialized true story that was first published here on The Lost & Found Story Box beginning in June of 2024.

Are you passionate about the connections between family history and food? If so, I invite you to visit my other newsletter, Culinary History is Family History. I’m filling that space with my own memories of family dinners and school lunches and recipes that have been passed down to me from the people I love most. And, I’m making room for you to do the same! See you soon.

The Lost & Found Story Box is reader-supported. When you buy through links on our site, we may earn an affiliate commission.

End Notes

1 U.S., War of 1812 Pension Application Files Index, 1812-1815 for Elias George

2 Year: 1840; Census Place: Perry, Alabama; Roll: 11; Page: 249; Family History Library Film: 0002334

3 Alabama, U.S., Civil War Soldiers, 1860-1865

4 “Terrible Affray: AN Old Feud Ended by One of the Parties Being Killed”, The Marion Times-Standard, Marion, AL, February 15, 1888, P. 4.

5 “Terrible Affray: AN Old Feud Ended by One of the Parties Being Killed”, The Marion Times-Standard, Marion, AL, February 15, 1888, P. 4.

6 “Terrible Affray: AN Old Feud Ended by One of the Parties Being Killed”, The Marion Times-Standard, Marion, AL, February 15, 1888, P. 4.

7 “Farmer Waylaid”, The Birmingham News, Birmingham, AL, December 12, 1907, P. 6.

8 “Farmer Waylaid”, The Birmingham News, Birmingham, AL, December 12, 1907, P. 6.

9 “Vet’s Plight Brings Shower of Letters”, Birmingham Post-Herald, Birmingham, AL, January 31, 1926, P. 23.

10 “Vet’s Plight Brings Shower of Letters”, Birmingham Post-Herald, Birmingham, AL, January 31, 1926, P. 23.

11 “Vet’s Plight Brings Shower of Letters”, Birmingham Post-Herald, Birmingham, AL, January 31, 1926, P. 23.

12 “Prohibition in Alabama”, The Encyclopedia of Alabama (https://encyclopediaofalabama.org/article/prohibition-in-alabama/)

That May-December marriage reminds me of a book I read many years ago, The Oldest Living Confederate Widow Tells All. I was a teenager ay the time and was horrified at the thought of it. 😂

I love your writing style! So engaging. I can’t wait to read part 2!