The remarkable service of William Eckman

More about George Gardner's friend, his military story and his connection to a Great Lakes legend

The surprising stories that almost got missed

Thanks so much for all the kind words and support I’ve received these last couple weeks as I celebrate the first anniversary of The Lost & Found Story Box here on Substack! It has truly been overwhelming.

After I published the final episode of The Epic Canoe Journey of George W. Gardner, a loyal reader mentioned she wanted to know more about William Eckman, the man who accompanied George Gardner on his 1883 trip down the Ohio and Mississippi rivers. I’d intentionally told the story of George’s point of view, which meant William was just a sidekick.

As I dug into William’s life and story, however, it became abundantly clear he was anything but a sidekick and had a fascinating tale of his own that deserved to be told. I’m thrilled to share that story with you, this week.

As we continue celebrating the one year anniversary of this space, this week we’ll be sharing the best lost & found stories in our teaser files or ancestor charts or hometowns, maybe even our imaginations! Head on over and join the conversations — and if you missed the earlier chats, jump in there, too!

Release Date: June 24, 2025

A story of duty, skill and survival

In 1866, Samuel H. Hurst, late commander of the 73rd Ohio Volunteer Infantry, compiled a complete history of the regiment from December 1861 until it was mustered out of service on July 20, 1865. Based on his personal journal, Hurst’s remarkable record helps to provides insight into William’s Civil War experience, and is used extensively throughout this retelling.

In the chill of mid-December 1861, some seven months after the start of America’s Civil War, 19-year-old William H. Eckman heeded President Abraham Lincoln’s call for able-bodied men to battle the Confederates and enlisted in the 73rd Ohio Volunteer Infantry. He’d been working as a telegraph operator in his hometown of Cleveland for a while by then, and thought his skills would be of value to the Union forces.

And he wasn’t wrong.

William’s technical skills immediately set him apart from other new recruits, and likely earned him the attention of Colonel Orland Smith and his staff at Chillicothe, OH. As the 73rd Ohio was mustered in, William was assigned the rank of sergeant in Company C. His dual responsibilities were laid out – he would lead a squad of men into combat while also serving as the company’s primary communication specialist.

At Camp Logan outside of Chillicothe, William learned the administrative, tactical and battlefield skills required of his rank, while also training recruits in military discipline; working with regimental signal officers to establish field telegraph procedures, and coordinat with civilian telegraph operators to maintain crucial lines of communication with state authorities.

Despite his previous experience, there was a lot for William to learn, and in a short period of time: The 73rd Ohio marched out of Camp Logan on January 24, 1862, headed for the rugged terrain of western Virginia.

Two weeks into their march, William and the 73rd Ohio had their first encounter with Confederate troops outside of Moorefield, WV.

It was near midnight on the 13th [February], when the head of our column reached the river at the ferry, four miles below Moorefield, and found that the ferry had been destroyed. The column halted, and the men began to build fires along the road, the night being quite cold. Suddenly a volley of rebel musketry, scarcely three hundred yards to our left front, startled the entire column, The balls came whistling sharply among us, wounding one of two men of regiment. The detachment of the cavalry in advance came tearing back through the column, almost producing a panic; but the infantry stood to arms, and, in a minute, out skirmishers were replying to the enemy’s fire, which was promptly silenced. Here was the first gun fired by the Seventy-third Ohio, and the first man of the regiment wounded.” 1

It’s not known how much action William and the men under his command saw that day, but in the weeks and months to come, they participated in sometimes daily skirmishes with the enemy, and several battles, including those at McDowell (May 8), Cross Keys (June 8) and Freeman’s Ford (August 22), all of which were Confederate wins.

William’s role as the 73rd Ohio’s communication specialist likely expanded greatly during these early months as he was called upon to maintain telegraph communication between the battlefield and headquarters, coordinate with railroad operators and other regiments to relay military intelligence, troop movements and ammunition needs as Union forces struggled to keep up with Confederate General Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson’s rapid maneuvers.

On August 28, the 312 men of the 73rd Ohio confidently marched toward what would come to be called the Second Battle of Bull Run as part of the 2nd Brigade, 1st Division, I Corps of the Army of Virginia under the command of General John Pope.

Two days later, on August 30, the 73rd Ohio was joined by the 25th, 55th and 75th Ohio regiments under General Nathaniel McLean, and charged with holding Chinn Ridge.

A chaotic and deadly battle ensued as waves of Confederate units advanced.

“The enemy in our front, moving in concert with those on our flank, came out of the woods – their line masking and overlapping our own. The whole left of our brigade poured into them a murderous volley. The combat grew fierce indeed. But the contest was not long. On came the flanking column. We stood until the enemy had nearly gained our rear, and had opened fire upon our flank. Then we retired.” 2

One-hundred and forty-four men of the 73rd Ohio were killed or wounded at Bull Run, and twenty others were taken prisoner,

William, however, was one of the lucky ones.

Which was a good thing – having lost 53-percent of the regiment, William was likely called on to help reorganize companies, train new recruits, instill military disciple, and ensure that supply lines and communications remained intact: In short, to help restore the 73rd Ohio to effective fighting strength.

The very fact of William’s survival, coupled with his battle-tested leadership skills and technical expertise, led to his rapid promotion following the Union loss at the Second Battle of Bull Run. In January 1863, he became Commissary Sergeant for the 73rd Ohio, and was transferred to Company H. There he managed food supply coordination, telegraph communications with supply depots and between company commanders and regimental headquarters.

Just one month later, 20-year-old William was promoted to 2ndLieutenant of Company H – a battlefield commission that reflected his increasing value to the 73rdOhio. As an officer, he would continue to perform his specialized communication duties, while also taking on additional responsibilities for training and leading men as the fighters of the 73rdOhio merged with the Army of the Potomac during their winter encampment.

On July 1, 1863, Second Lieutenant Eckman and the 73rd Ohio approached the site of what history would record as one of the bloodiest and significant battles of the war, Gettysburg, PA. By then, William had been an officer for nearly five months and had proven himself invaluable during the Unions chaotic loss at Battle of Chancellorsville, VA (April 30-May 6), maintaining telegraph links during the retreat, helping to reorganize scattered soldiers and managing emergency resupply.

Those skills would be sorely tested in the coming days.

The 338-man strong 73rd Ohio spent much of the first two days and nights of the epic battle fighting in and around Cemetery Hill, targeted by Confederate sharpshooters and enduring hours of deadly shelling and cannon fire. The first night William and his comrades slept among the gravestones.

“At ten o’clock at night, we were again relieved, and retired to the hill where we lay down and slept heavily after the fatigue of the day. We lay on the grass among the neatly-trimmed graves; and some, with no irreverence, rested their heads on the green hillocks for pillows, slept without a superstitious dream, but with the assurance that tomorrow’s sun would bring earnest and bloody work.” 3

The next night, sleep was harder to come by: Of the roughly 100,000 men on the field of battle that day, some 20,000 had been killed, wounded, missing or captured.

“During the night, we could hear cries of hundreds of wounded and dying men on the field, in our left front, where Hancock repulsed the foe. It was the most distressful wail we ever listened to. Thousands of sufferers upon the field, and hundreds lying between the two skirmish lines, who could not be cared for, through the night were groaning and wailing and crying out in their depth of suffering and pain. They were the mingled cries of friend and foe, and they were borne to us on the night-breeze, as a sad, wailing, painful cry for help.” 4

Day Three of the battle started out much as the previous days, with the 73rd Ohio defending the batteries on Cemetery Hill against heavy and relentless Confederate shelling. Mid-afternoon, however, the battle shifted as 12,500 members of the Confederate infantry attacked the low ridge at the northern edge of Cemetery Hill in what came to be called Pickett’s Charge. In a fierce fight, Union forces valiantly repelled the attack, dealing a crushing blow to the Confederates, and claiming their hard-fought victory.

By the next morning, 87 years to the day of America’s founding, Confederate troops were in retreat.

“Who shall say that on this day the Nation was not born anew? For, by the morning light, we could see the enemy’s trains winding through the mountain pass toward Hagerstown; and we knew that the field of Gettysburg was ours. The enemy showed no disposition to renew the conflict, but still held his lines while his trains were moved to the rear. We seized the opportunity, as far as possible, of caring for our wounded and burying our dead.

The loss on both sides had been very great; but that of the enemy much greater than our own. The loss in our own regiment had been severe indeed; we went into the fight with scarcely three hundred men, and lost, in killed and wounded, one hundred and forty-four. It was more than sad, to see so many of our noble comrades this mangled. But we were proud to have seen them do their duty and bear themselves like men. Our little battalion had stood, for three days and nights, in the front line, among those faithful guardians of our batteries on the hill; and though we had lost half our number, still we had done our duty.” 5

As 1863 came to an end, William completed his second year of service, and he and the other enlisted men of the 73rd Ohio became eligible to re-enlist. In his history of the regiment, Samuel noted:

“There was an anonymous desire that the regiment should not be divided, but should re-enlist as a regiment, with comparative unanimity, or not at all.” 6

And, that’s what happened: Of the 230 original members, 225 re-enlisted, including William.

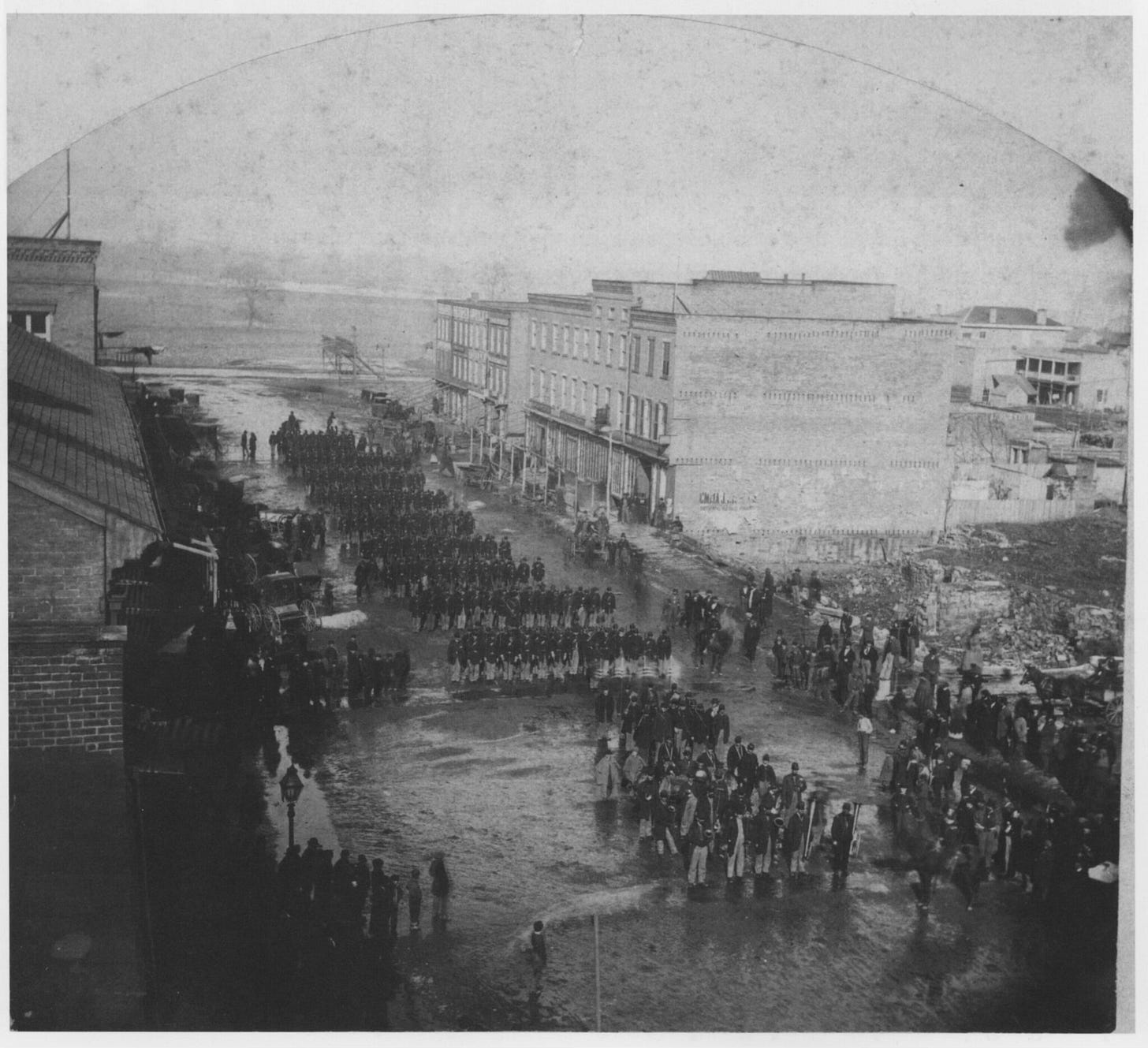

As part of their re-enlistment package, the men of the 73rd Ohio were granted a 30-day furlough, and on January 4, 1863, they left Outlook Valley, TN and traveled by train back home to Chillicothe, arriving on the 15th to a grand homecoming celebration.

The next day, William was back home in Cleveland with his parents.

Sometime during that month at home, William came to either make or renew the acquaintance of 26-year-old Elizabeth Minner, the daughter of Samuel and Mary (Queen) Minner of Wellsville, OH, some hundred miles south-east of Cleveland along the New York border. Where or even how the two met is unknown, however, it’s possible Elizabeth was in Cleveland staying with her pregnant older sister, Margaret Jane, while her husband, James Bennett was, like William, away at war.

On February 15, William’s furlough ended, and he returned to service two weeks later as the newly-appointed First Lieutenant and Quartermaster in the 73rd Ohio. This new role required him to take on critical logistical responsibilities including overseeing all supply, transportation and communication for the regiment during the demanding Atlanta Campaign.

The goal of General William T. Sherman’s Atlanta Campaign was to occupy Atlanta, GA, sever supply and transportation lines, split the Confederacy, and cripple their ability to wage war. It was an ambitious goal, and one which would take more than four months to accomplish.

The logistical challenges would be monumental for regimental quartermasters like William.

They were responsible for maintaining supply lines under constant movement, securing and distributing provisions and replacing lost or damaged equipment, managing medical and evacuation logistics and coordinating with other units and headquarters, all while adapting to enemy actions in enemy-occupied lands.

The Atlanta Campaign began on the morning of May 2, 1864, when 318 members of the 73rd Ohio marched out of Lookout Valley near Chattanooga, TN, under the command of Lieutenant Colonel Samuel Hurst.

“The men were in excellent condition and spirits, and went forth with a willingness and a confidence of success that was in itself a presage of victory.” 7

Attached to the Army of the Cumberland and fresh from furlough, William and his fellow Ohioans quickly found themselves in the thick of things. In the first 19 days of the campaign, they fought three battles — Rocky Face Ridge, GA (May 7-12), Resaca, GA (May 13-15), and New Hope Church, GA (May 25-26), the last of which was both fierce and costly for the 73rd Ohio.

We had not advanced fifty paces when we were greeted by a volley from the enemy's line of battle. Under such a fire as now poured in upon us, it was simply impossible to advance; at best, we could only maintain our position, and return the enemy's fire… The Seventy-third was greatly exposed, and suffered severely from the bitter fire it was compelled to receive. 8

With another 80 miles to Atlanta stretching out before them, the 73rd Ohio battled their way south through Georgia, seeing action at Pine Mountain, GA (June 15), Kennesaw Mountain, GA (June 27) and, after celebrating the nation’s birthday with short speeches and “home melodies, calling back into memory the pleasant associations of the peaceful past, and awakening in our hearts new longings for home”, Peachtree Creek (July 20). 9

Finally Atlanta was within reach.

Thinking the Southern industrial and supply hub had been abandoned, the divisions of Sherman’s Army raced to be the first to enter, only to be greeted by Confederate skirmishers and artillery fire. The Battle of Atlanta ensued, with Union troops repeatedly being pushed back, before eventually surging forward with overwhelming force and inflicting massive, unacceptable casualties on the enemy to win the day.

Capturing the city would, however, take another 41 days of prolonged fighting and siege warfare that ended with the Confederate abandonment of Atlanta on September 1.

And so, at last, Atlanta is ours. The rebel infantry had evacuated the place the night before the sounds we heard as of cannon, being the explosion of great stores of artillery ammunition, which they themselves destroyed. Three trains eighty-four cars in all loaded with artillery ammunition, ordinance and other war material were destroyed by them, together with four engines, and an extensive foundry, where vast amounts of ammunition for cannon had been manufactured. 10

In his report to Washington, Samuel Hurst praised the effort and sacrifice of the 73rd Ohio to his superiors:

“The campaign has been a severe one, the loss to this command in killed and wounded alone being 210 men and 8 officers, but the courage, the gallantry, the endurance, and determination of officers and men alike have proven their high soldierly capabilities, while the confident spirit of our troops gives full assurance that to our noble army Atlanta is but the "Gate City." 11

For most of the next two months, William and the 73rd Ohio remained in Atlanta, fortifying defenses around the city and marshalling supplies. With the railroads and most roads destroyed, no supplies could be brought forward, and food for both troops and animals were running low. In response, expeditions were sent out into enemy territory to forage, including one which included members of the 73rd Ohio.

“We were gone four days and brought in nine hundred wagonloads of corn; besides, the men got enough sweet potatoes and fresh meat to make them happy for a fortnight.” 12 P 152

Shortly after, Sherman’s army abandoned Atlanta, burning public buildings, warehouses and transportation infrastructure on their way out as they began their March to the Sea.

“We left Atlanta in flames Atlanta in flames. It was the avowed purpose to burn all those buildings that could rend the place valuable in a military point of view, should the enemy reoccupy it. In doing this, many other buildings were burned, and more than half the city was left in ruins.” 13 p154

Whether William was among the members of the 73rd Ohio to march out of Atlanta on November 13, 1864 or not is unknown. Since his furlough the previous year, he and Elizabeth Miner had been exchanging letters and, had fallen in love.

William had sought and obtained permission from his commanders to temporarily return to Cleveland and marry Elizabeth, and on Tuesday, November 22, the two were wed in a simple ceremony before the the Cuyahoga County clerk in Cleveland.

Seventeen days later, on December 9, William rejoined the 73rd Ohio at their camp, some 13 miles outside Savannah, GA.

And, he’d arrived just in time. Confederate forces had broken Sherman’s “cracker line” preventing his troops from getting fresh food, supplies and equipment, and had also disrupted communication lines between Sherman and his counterpart, General John Foster, commander of the Department of the South.

Ten days after William’s return, the situation had been mostly resolved.

“Our first rations were received via the Ogeechgee River on the 19th, and found our men growing very weak, as they had lived, for six days, on their gill of rice per day, and having nothing but swamp water to drink, the change to coffee and crackers was most welcome indeed.” 14 P 163.

About that same time, twenty tons of eagerly awaited mail arrived and was distributed to the men of Sherman’s army. Among the envelopes was likely one from Mrs. William Eckman, relating the news that her younger brother, 21-year-old Harrison Minner, had been killed in action during the Battle of Franklin, TN (November 30).

What Elizabeth didn’t include in her letter, and perhaps didn’t even know, was that she and William were expecting a child.

On December 21, 1864, Savannah surrendered. Sherman’s March to the Sea was done.

“Thus ended successfully one of the most daring and masterly military campaigns in all history. An army of seventy thousand men had destroyed its own communications for a hundred miles to its rear — had marched out of its fortified position, and away through the very heart of the enemy’s country, three hundred miles, to its farther border — marching leisurely, as if they had been on a pleasure trip, and had there established a new base, compelling the surrender of one of. the principal commercial cities of the country; and all this had been accomplished with scarcely a skirmish or an interruption. Well was it proven that the Confederacy was “a shell” — that, though strong in agricultural resources and the labor of its slaves, its men were exhausted. And now the Confederacy had been virtually severed by the war-path of the victorious Sherman, whose sweeping columns had destroyed two hundred miles of railroad, burned many millions worth of cotton and made four black belts across the State of Georgia.” 15

Following the successful conclusion of his March to the Sea, General Sherman and the 73rd Ohio turned their attention to the Carolina Campaign. On March 16, 1865 they participated in the Battle of Averysboro, NC, and three days later, the Battle of Bentonville (March 19-21), the final battle of the campaign.

Nine days later, on March 30, William did the unexpected, officially resigning from the 73rd Ohio, a complex process which he’d likely initiated weeks earlier, as it required sign off by regimental, brigade, departmental and Department of War officials as well as as a complete audit of the regiment’s quartermaster books.

Shortly after, William returned to Cleveland, where he likely received the news on April 9th that Confederate General Robert E. Lee had signed the Articles of Surrender Agreement of the Army of Northern Virginia.

The war to which William had given four years of his life, was finally over.

Back in Cleveland, William returned to his old job at the telegraph office, and on September 7, 1865, Elizabeth gave birth to their son, Georgie, at the home the couple shared with her in-laws, Henry and Laura.

In 1870, William left the telegraph office and became a traveling agent for the Cleveland publishing house of Sanford & Hayward, a position he held until 1874 when he took over ownership of a local newspaper, likely relying on many of the same administrative and people skills he’d honed in the military.

Then in 1876, tragedy struck when 11-year-old Georgie contracted diphtheria. William’s and Elizabeth’s only child passed away on October 2.

Grief-stricken, William turned to art and community service to both fill the void and escape the darkness. In 1876, he helped found the Cleveland Art Club, and in 1878, he was elected Cleveland’s City Clerk, a position he would hold for seven years.

He and Elizabeth bought a home on Cleveland’s Mansion Row, and became neighbors to George Gardner and his wife, Rosaline. In 1880, both men were instrumental in the formation of The Cleveland Canoe Club, and three yers later, they would embark on their epic journey down the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers.

William retired from public service in 1885, and returned to the newspaper business and the publishing world, first in Cleveland and later in Chicago and New York.

It was in the latter city where, on October 6, 1901, William passed away at the age of 59. The night before his death, he and George Gardner had enjoyed a fine meal together, and made plans to meet later that week back home in Cleveland.

Please hit the ❤️ button at the bottom of the page to help this story reach more readers. And if you’re not already a subscriber, I’d love to have you join me. Thanks!

William’s strange Lake Erie encounter

An hour before sundown on Monday, August 14, 1882, William Eckman and two other members of the Cleveland Canoe Club were out for a paddle on Lake Erie when suddenly an ominous dark line appeared some four hundred yards to the northwest of them.

The men stilled their paddles and watched in horror as the line turned into a form, and the form “turned forward like a huge eel…and, with a continued, unbroken motion, the large creature moved a military course for about eight rods in perfect outline.”

William and his companions would later describe the creature as being 35 feet long from head to tail and some two and a half feet around. In form, it resembled a snake in the front and an eel in the back, tho the tail was replaced by horny spikes. And the head of the creature, well that was enormous and “square and blunt like a cow’s, though smaller than the body in size.”

In color, the sea monster was “very dark, almost black, and the belly of the same color with a slight yellow tinge, and both formed in perfect contrast and were not mixed, as in the body of the spotted snake.”

As the canoeists watched, the creature “moved toward the place where they were resting in their boat, with a slow surrounding circle like the wake of a drifting steamer, and lashed the water regularly. Slowly, and with a swaying yet continuous, unimpeded and gliding movement, it appeared to turn completely over and then swept out of sight.”

Terrorized at what they’d just witnessed, the three men put paddle to water, frantic to get to the safety of shore before the creature reappeared.

They were too slow.

“The foaming rush of the monster was tremendous, and he moved forward with apparent ease and unconcern. The last time, he turned over like a duck, his back in the air and his tail and horns under. The dark line beneath the water was visible for at least one hundred feet, and the observers shuddered and held their arms. A moment more, and nothing was to be seen but a grand and solemn ripple. He had gone.” 16

Stunned, William and his friends paddled to share, confident they had come face to face with the legendary Lake Erie sea serpent.

One of the earliest documented encounters with the Lake Eric sea serpent was reported on July 30, 1818 by Theodore J. Shaver, master of the sloop Speculation.

“I discovered at a distance of about a mile from the vessel, the lake being very smooth about us, a violent moving of the water. I immediately gave the alarm, being the only one on deck at the time, when all on board, both sailors and passengers, came immediately above. At first it was supposed to be a water spout, but soon, on its approaching us nearer, we discovered to our great surprise, that it was a species of the wonderful sea serpent. Its head and tail were erect and raised at equal distances from the water, which was as near as we could judge, about 50 feet.

“The people on board were much terrified as it advanced, each thought themselves the object on which it was determined to feast. Those who had the courage immediately left the deck and sought refuge in the recesses of the bale, while those who were resolute felt determined to stand their ground, and give their common enemy a formal reception, they therefore prepared themselves with such weapons of defense as could be found on board, and waited the unprovoked attack.

“In the meantime, the serpent, with all that energy, which is natural to his Satanic majesty’s subjects, approached the barge, and when within about ten rods of the ship, he stretched his head forward as though her was anxious about his choice – not observing Captain Shaver on deck (as he had made his escape at the first appearance of the serpent, among the casks below), set forth his forked tongue and hissed out all the damning curses he was master of, then turning , lashed the water with his tremendous tail, util it foamed as when agitated by the most violent gale, he then immediately disappeared, and was not afterward seen on our voyage.” 17

And a decade after William’s encounter with the creature, two fishermen reported seeing something strikingly similar to what William had seen, this time near Locust Point, 90-miles due west of Cleveland on the shores of Lake Erie.

Described as being “about twenty-five feet long an about one and one-half feet in diameter through the largest part”, the sea serpent’s head was long and flat, and “about five feet from its head there appeared to be several large fins or flippers”.

Like the one William had seen, this creature was black with mottled brown spots and “did not offer to molest the men but swam out into deeper water, where it has not been seen since.” 9

In the decades since, scores of people have claimed to see the Lake Erie sea serpent. So many, in fact, that the creature has been given a name, South Bay Bessie, and is celebrated far and wide across the greater Cleveland area.

Copyright 2025 Lori Olson White

Have you read the incredible true story of Aimee Henry and Mary Martha Parker? Call Me a Bastard is my longest serialized story to-date, and the one that started it all here on the Lost & Found Story Box. Check out the story from the beginning.

The Lost & Found Story Box is reader-supported. When you buy through links on our site, we may earn an affiliate commission.

End Notes

1 Hurst, Samuel H, Journal History of the Seventy-third Ohio Volunteer Infantry, 1866, Internet Archives. P. 11.

2 Hurst, Samuel H, Journal History of the Seventy-third Ohio Volunteer Infantry, 1866, Internet Archives. P. 40.

3 Hurst, Samuel H, Journal History of the Seventy-third Ohio Volunteer Infantry, 1866, Internet Archives. P. 69.

4 Hurst, Samuel H, Journal History of the Seventy-third Ohio Volunteer Infantry, 1866, Internet Archives. P. 73.

5 Hurst, Samuel H, Journal History of the Seventy-third Ohio Volunteer Infantry, 1866, Internet Archives. P. 76.

6 Hurst, Samuel H, Journal History of the Seventy-third Ohio Volunteer Infantry, 1866, Internet Archives. P. 112.

7 “73rd Regiment Ohio Volunteer Infantry”, Ohio in the Civil War, https://www.ohiocivilwarcentral.com/73rd-regiment-ohio-volunteer-infantry/.

8 Hurst, Samuel H, Journal History of the Seventy-third Ohio Volunteer Infantry, 1866, Internet Archives. P. 129-131.

9 Hurst, Samuel H, Journal History of the Seventy-third Ohio Volunteer Infantry, 1866, Internet Archives. P. 137-138.

10 Hurst, Samuel H, Journal History of the Seventy-third Ohio Volunteer Infantry, 1866, Internet Archives. P. 148.

11 Hurst, Samuel H, Journal History of the Seventy-third Ohio Volunteer Infantry, 1866, Internet Archives. P. 150.

12 Hurst, Samuel H, Journal History of the Seventy-third Ohio Volunteer Infantry, 1866, Internet Archives. P. 1152.

13 Hurst, Samuel H, Journal History of the Seventy-third Ohio Volunteer Infantry, 1866, Internet Archives. P. 154.

14 Hurst, Samuel H, Journal History of the Seventy-third Ohio Volunteer Infantry, 1866, Internet Archives. P. 163.

15 Hurst, Samuel H, Journal History of the Seventy-third Ohio Volunteer Infantry, 1866, Internet Archives. P. 165.

16 “Columbia’s Snake: The Great National Serpent Seen in Lake Erie. A Geographical Monster Appears Off Cleveland—Wonderful Actions of the Huge Reptile”, The Cleveland Leader, August 15, 1882, P. 8.

17 “The Lake Serpent”, The Cleveland Register, Cleveland, OH, July 31,1818, P. 2

18 “Lake Erie’s Sea Serpent: Said to Have Been Seen By Fisherman Near Oak Harbor, “ The plains Dealer, Cleveland, OH, May 21, 1892, P. 4.

I have never heard of the Lake Erie serpent!

Eckman's Civil War service is mighty impressive and he went on to have an impressive career. But the bonus here for me is the eyewitness account of the Erie sea serpent. I've been doing research for months on Mishebeshu. Recently I acquired a painting by Rabbet Strickland, an Ojibway artist from northern Wisconsin of this mythical creature. The description matches perfectly!