The Curious Case of Eddie Krajic, Alexander Watson & Judge Adolph Sabath

A tenacious child, an unethical attorney and a progressive justice

Release Date: June 3, 2025

A tenacious youth

On a winter day in January 1898, 13-year-old Eddie Krajic appeared before Justice Adolph Sabath of Chicago's Police Magistrate Court.

"Your Honor, I wish to swear out a writ of attachment," Eddie announced, his voice clear and unwavering despite his youth.

Justice Sabath couldn't hide his surprise. "You make that request just like a full-fledged attorney," he remarked, "but what do you know about attachment writs?"

The boy responded without hesitation: "O, I know everything about such writs. I'm somewhat of a lawyer myself, and some day I hope to be a great one. I have been reading law considerably."

Thus began a curious legal dispute – a case that pitted a child laborer against his employer in an era when such confrontations rarely made it to court, let alone received coverage in the Chicago Tribune. 1

But Eddie was no ordinary child laborer. Whereas many children his age worked in Chicago’s meatpacking plants, sweatshops and factories, or hawked newspapers – Judge Sabath himself had begun his career as a courier, Eddie had spent the previous six months working as an office boy for Alexander Hamilton Webster, a local attorney.

And in the process, he’d absorbed enough legal knowledge to make him, in his own words, "dangerous."

The issue was backpay.

Eddie’s employer had promised him $2.50 a week – a modest sum, but not insignificant for a child, considering unskilled adult laborers were earning $10 to $15 a week in Chicago at the time. However, Webster had fallen behind on his payments, and now owed Eddie $3.50, about $120 in today’s currency.

Rather than accept the loss, Eddie had decided to use the legal knowledge he’d gained in Webster's employ to seek justice in the form of a writ of attachment.

Please hit the ❤️ button at the bottom of the page to help this story reach more readers. And if you’re not already a subscriber, I’d love to have you join me. Thanks!

An unethical attorney

What Eddie couldn't have known was his employer's checkered past. At 47, Alexander Hamilton Webster was what 19th-century Americans might have called a "ne'er-do-well" – a man who had squandered both advantages and opportunities, and repeatedly made bad decisions.

The only son of Thomas M. Webster, a prominent attorney in Lockport, NY, Alexander was still a law student when his father died in 1872, reportedly leaving him an inheritance of $40,000, well over a million dollars today.

While Alexander did complete his law degree and become an attorney, he also proved unable to manage his inheritance.

After moving to Chicago in November 1877, he reportedly lost his entire fortune speculating in the grain market – a common path to ruin in the volatile markets of post-Civil War America. Eighteen months later, his inheritance gone, Alexander showed up back in Lockport and restarted his law practice.

He also became a family man, marrying Julia Ferguson, the middle daughter of a local druggist, and quickly welcoming a daughter.

For a time, it appeared Alexander’s bad decisions were behind him, but, alas, they weren’t.

A.H. Webster, a prominent young attorney of Lockport, was [April 30, 1885] indicted by the grand jury for grand larceny in the second degree, for appropriating $180 of a loan negotiated for a client.

This case, on account of the high social standing and connections of the prisoner, caused very great excitement in Lockport. Webster, about seven years ago, had a fine law practice and $40,000 left him by his father’s death, but he became infected with the speculative fever, and moving to Chicago lost all in eighteen months. He came back, and has since practiced law.

Another client charges that he has appropriated $1,300 of money collected for her, and there are other cases reported. It is probable that the money has been used in speculation. Webster, who has a fine family, has been in jail for three weeks past, unable to obtain bail. 2

In the end, Alexander’s family and friends stepped in and, “made good the losses occasioned by his rascality," as Buffalo’s Evening Telegraph bluntly put it, and the charges were set aside. 3

Alexander was a free man, but he was disgraced.

And he was also alone: Although it appears Alexander remained in Lockport for the next several years — in 1887 there were rumors he’d committed suicide, he was no longer living in the family home.

And by 1889, he had all but disappeared.

A.H, Webster, an indigenous lawyer formerly known by everyone here, but whose recent whereabouts have been a cause of considerable speculation, is engaged in the insurance business in Kansas City. 4

Four years later, and in Alexander’s absence, Julia sought and was granted a divorce.

Two Lockport ladies were relived of husbands this week. One of those ladies in Mrs. Julia E. Webster, who is residing with her mother on Washburn Street. Her husband, A. Hamilton Webster, was formerly a lawyer here, but fell into dissolute ways and dropped in the social and business scale and he migrated to the West. 5

It’s unclear when Alexander returned to Chicago, but return he did, because at some point during the summer of 1897, he hired Eddie Krajic, promised to pay him $2.50 a week to serve as his office boy, and then failed to follow through.

A progressive judge

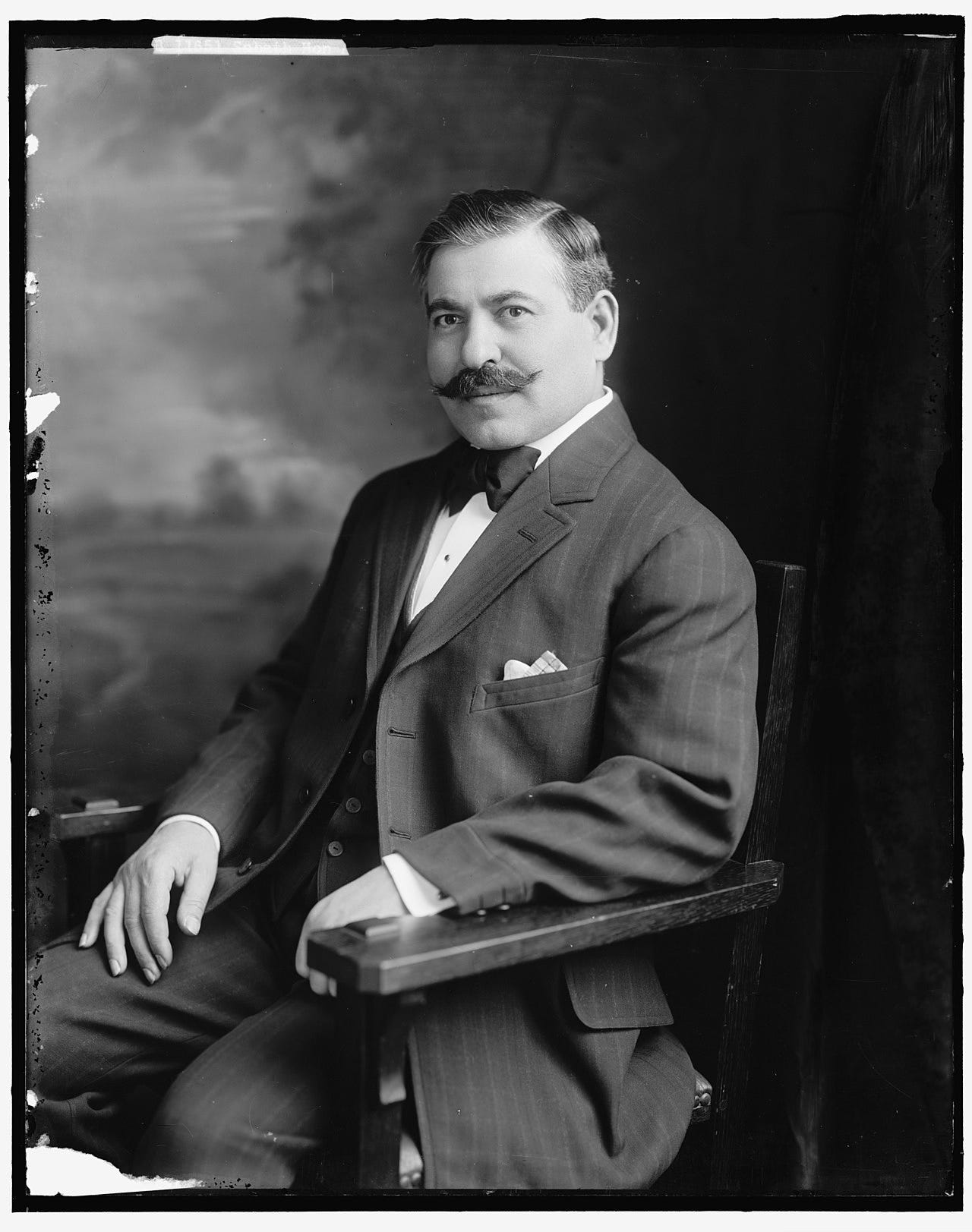

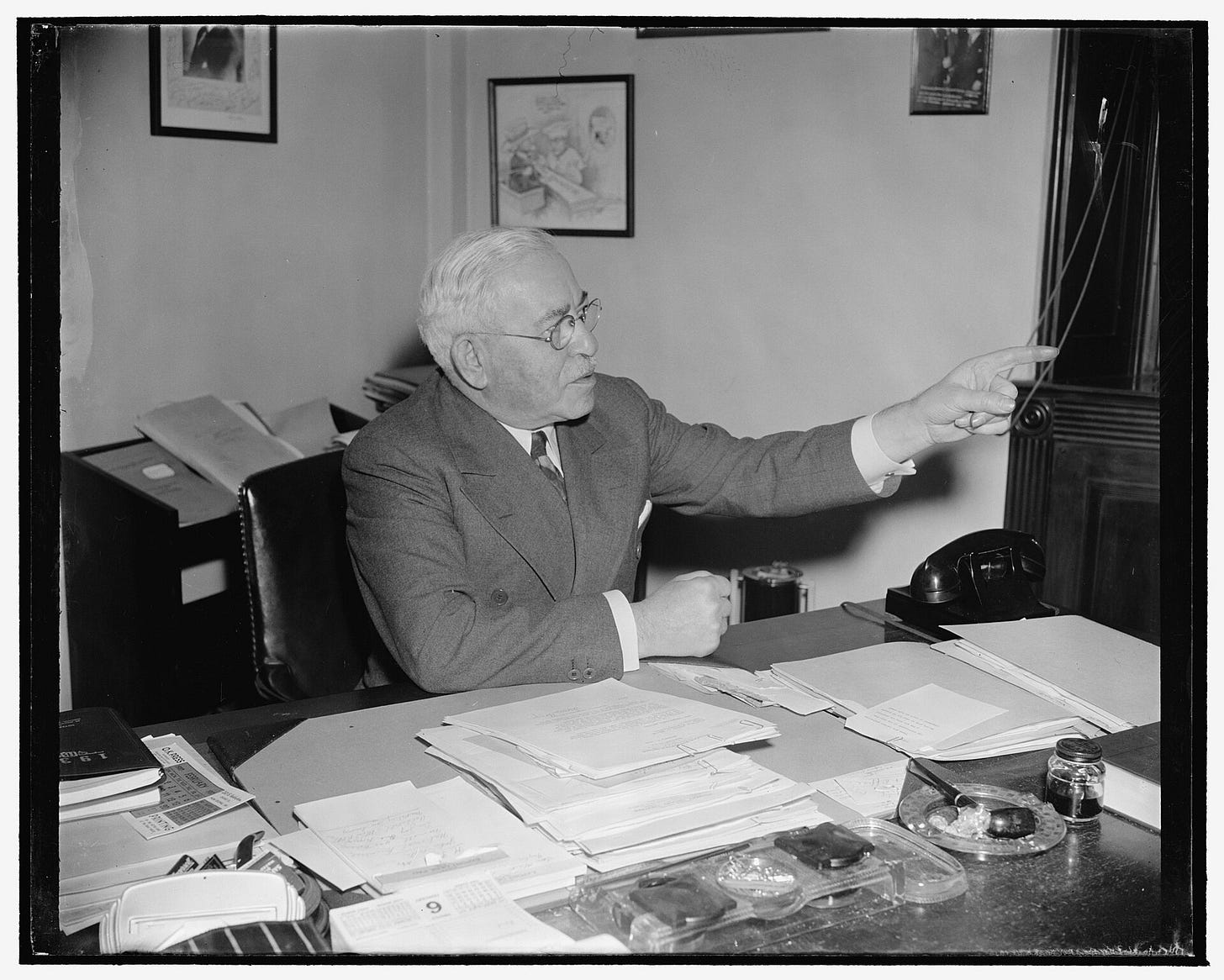

The third figure in this curious legal triangle was 36-year-old Adolph Joachim Sabath, justice of Chicago’s Police Magistrate Court.

Born in Bohemia in 1866, Adolph had arrived in America just twenty years earlier, alone and penniless, but determined to be successful.

And he was.

He’d worked his way through law school, and, after graduating from the Chicago College of Law in 1891, had quickly entered public service, organizing the east European Jewish electorate on Chicago’s west side. 6

As Adolph’s political and social influence grew, so did his opportunities. In 1895, he was appointed Justice of the Peace, and two years later, began what would be a nine-year stint as Justice of Chicago’s Police Magistrate Court, where he adjudicated minor criminal offenses and civil disputes like the one Eddie Krajic boldly brought before him in early 1898

The legal battle

When Eddie presented his request for a writ of attachment against Alexander’s furniture and books, Justice Sabath raised the obvious legal obstacle: "But the law does not allow me to grant you a writ. You are too young."

Having anticipated this objection, Eddie was prepared with a solution: "O, I am well aware of that fact, and I wish to bring the suit through my next friend, J.K. Tenant, as prescribed by the law, and he is here." 7

Whoever J.K. Tenant was, Eddie’s reference to him as a "next friend" must have been a clear indication to the judge that the young office boy knew what he was talking about. The concept of "next friend" (or prochein ami in legal terminology of the era) was a procedural mechanism that allowed minors like Eddie to bring suit through an adult representative, and would have been required under the circumstances.

Impressed by Eddie’s preparation, and convinced that he had a solid case, Justice Sabath issued the writ of attachment. Court constables were dispatched to seize Alexander’s furniture and books, ending in what must surely have been a public humiliation for the attorney and a remarkable victory for tenacious office boy.

The immediate outcome of Eddie's suit against Alexander isn't recorded in the surviving accounts. Whether he recovered his $3.50 in wages remains unknown, lost to history like so many everyday disputes of the era.

What we do know is that despite his early legal promise, Eddie never realized his ambition of becoming "a great lawyer." The 1900 census, just two years after his courtroom appearance, records him working as a machinist helper — a respectable trade, but far from the legal career he envisioned.

By 1910, Eddie had found work as a yardmaster for the railroad, and the 1920 census lists him as a railroad clerk. His life was cut tragically short on January 27, 1929, when he died at just 44 years of age, leaving behind a wife and two daughters.

Alexander remained in Chicago for the next few years, and appeared in the 1900 census as one of ten people living at a State Street boarding house headed by Adelaide Gillette. He was still working as an attorney.

Sometime before 1920, Alexander moved to Buffalo, where he opened a small law office, became a volunteer firefighter, and, it would seem, successfully turned his life around. He died in 1930 at the State Fireman’s Home. He was 79.

Adolph, meanwhile, went on to the most distinguished career of the three. Elected to Congress in 1907, he served continuously until he died in 1952—a remarkable 45-year tenure. Throughout his congressional career, Adolph maintained the progressive values evident in his handling of Eddie's unusual case, advocating for immigrant rights, Prohibition repeal, and New Deal policies.

Copyright 2025 Lori Olson White

Have you read the incredible true story of Aimee Henry and Mary Martha Parker? Call Me a Bastard is my longest serialized story to-date, and the one that started it all here on the Lost & Found Story Box. Check out the story from the beginning.

And in case you missed it, here’s a link to my most popular short series to-date, The Incorrigible John George. I hope you’ll agree that “incorrigible” is the best way to describe this old scoundrel!

The Lost & Found Story Box is reader-supported. When you buy through links on our site, we may earn an affiliate commission.

End Notes

1 “Boy Proves a Good Lawyer: Eddie Krajic, 11 Years Old, Surprises Justice Sabath by His Legal Knowledge”, Chicago Tribune, (Chicago, IL) January 18, 1898, P. 8.

2 “A Lockport Attorney’s Doings”, Buffalo Courier Express, (Buffalo, NY) May 3, 1885, P. 8.

3 “Lockport”, The Evening Telegraph, (Buffalo, NY) May 4, 1885, P. 2.

4 “Lockport”, Buffalo Courier, Buffalo, NY, February 24, 1889, P. 7.

5 “Lockport”, The Buffalo Morning News, Buffalo, NY, July 16, 1893, P. 3.

6 “October 31 Open Meeting: The Politics of Chicago Jewry, 1850-2004, Chicago. Jewish History, Chicago Jewish History, Vol. 28, No. 4, Fall 2004, P. 14.

7 “Boy Proves a Good Lawyer: Eddie Krajic, 11 Years Old, Surprises Justice Sabath by His Legal Knowledge”, Chicago Tribune, (Chicago, IL) January 18, 1898, P. 8.

Thanks for another amazing, well-researched story, Lori! I need to catch up on the others you mention.

Wow- what a remarkable legal case, particularly for the time period. David vs Goliath. Never give-up