The Epic Canoe Journey of George W. Gardner: PART 3

Preparations, Challenges and Lessons of and on the Mighty Mississippi River System

Before you start reading Part 3, make sure you’re all caught up!

Release Date: April 15, 2025

The River Defies All Masters

Several months before George Gardner hoisted the City of Cleveland into the rushing waters of the Ohio River in Cleveland, OH, Samuel Longhorn Clemens, better known as Mark Twain, published what would become one of his most popular books, Life on the Mississippi.

Filled with Twain’s trademark humor, unexpected adventure, and nuanced observations of life along the riverbanks, the 624-page book helped shape the romantic image of river travel, elevating it from mere transportation to a form of engagement with the American spirit itself.

"The face of the water, in time, became a wonderful book--a book that was a dead language to the uneducated passenger, but which told its mind to me without reserve, delivering its most cherished secrets as clearly as if it uttered them with a voice. And it was not a book to be read once and thrown aside, for it had a new story to tell every day." 1 ~ Mark Twain

Whether George read Life on the Mississippi before embarking on his journey or not, the sentiment was definitely something he would have appreciated.

He'd spent years paddling and exploring the Ohio and Cuyahoga rivers, had worked extensively throughout the Great Lakes on steamboats and sailing ships, was a competitive canoer and avid yachtsman, and a man who loved a good challenge.

And, as George would find out rather quickly, canoeing the Mississippi River would definitely be a challenge.

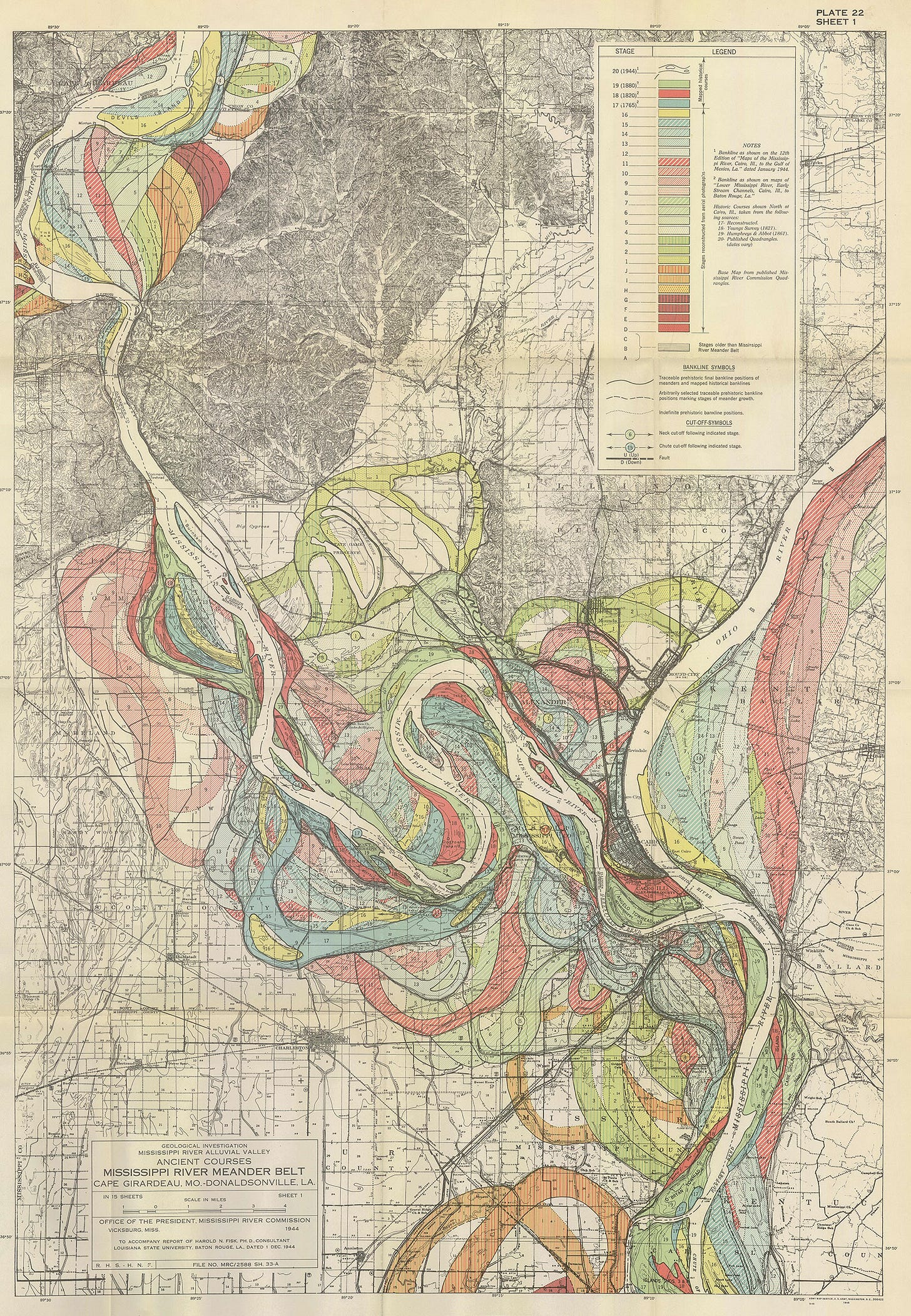

The lower Mississippi is a monster, which has ever defied and probably always will defy man’s efforts to restrain or keep it within bounds. Its channel is constantly shifting, invariably tending westward. In time—if time lasts long enough—the Mississippi Valley will be somewhere in the Pacific Ocean, and the future canoer will not miss the corn, cotton, and sugar (fringe of the river banks).

The winds in the Mississippi Valley are as regular as grandfather’s clock. They have no occasion for weathervanes in that section, as it always blows one way up stream (bear in mind we are going down).

The river is very crooked, at times doubling upon itself for miles, but it’s a fact, and I’ll produce our log to substantiate it, that the wind was always dead ahead regardless of bends, crooks, turns, angles, or sinuosities. This wind usually sets out in the Gulf of Mexico as an innocent zephyr, freighted with the fragrance of the tropics; as it approaches the confines of northern civilization it grows as formal and stiff as a Presbyterian elder; later on, that is to say higher up, it develops into masses of frigid ozone and finally terminates in that exclusively northern production known as a cyclone.

On the occasion of our cruise, however, a special dispensation seems to have been ordered, and we had more cyclones than zephyr by a very large majority. ~ George W. Gardner 1

Please hit the ❤️ button at the bottom of the page to help this story reach more readers. And if you’re not already a subscriber, I’d love to have you join me. Thanks!

Navigational Wisdom from a Fellow Voyager

Lucky for George, he had a secret weapon when it came to getting to know and understand the unpredictable river system prior to his departure: friend and fellow canoe enthusiast, Dr. Charles Neide.

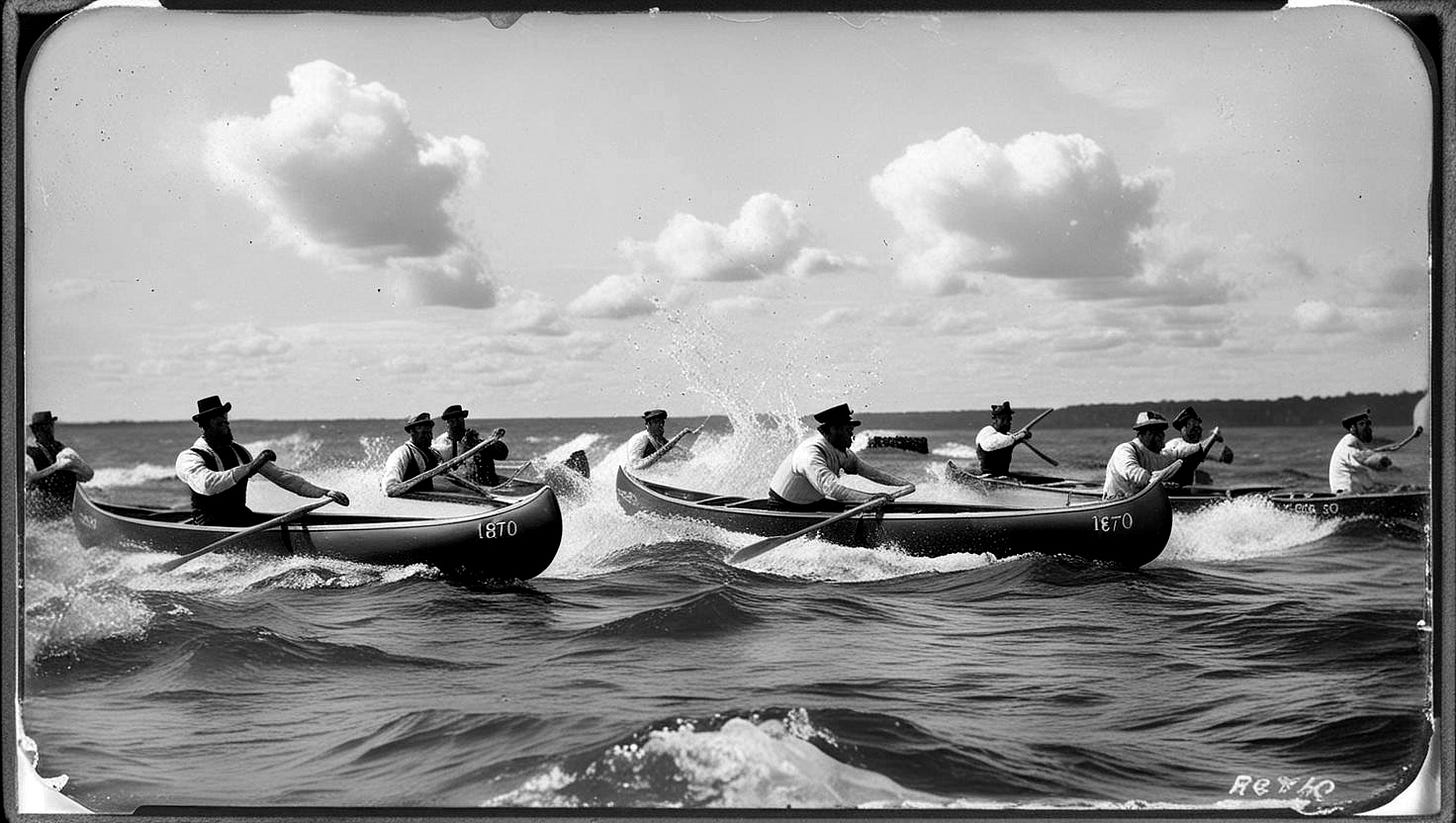

In August of 1882, Charles and his companion, S.D. “Barnacle” Kendall, had embarked on an epic adventure of their own – and one which had likely inspired George to plan a similar journey.

It was an impressive undertaking which saw the 36-year-old dentist and the retired sea captain canoeing from Lake George, NY to Buffalo, NY via the Champlain and Erie Canals, traversing Lake Erie to Cleveland, OH, paddling through the Ohio Canal to Portsmouth, OH, joining the Ohio River, which joined the Mississippi River in Cairo, IL, venturing out into the Gulf of Mexico in New Orleans and finishing in Pensacola, FL.

The nearly six-month journey covered an estimated 3,300 nautical miles, and passed through some of the same waters which George would navigate the next year.

It’s known Charles took meticulous notes: In 1885 he published a full account of his adventure in a book titled, The Canoe Aurora: A Cruise from the Adirondacks to the Gulf. So, it’s possible he shared his navigational charts and documents with George, and perhaps even provided him with mile-by-mile insights — all of which would have been invaluable.

Beyond whatever assistance Charles may have offered, George’s river education would surely have been enhanced by interactions he had with people he met along the way, as well —steamboat pilots with specialized knowledge of channel locations, ferrymen who crossed the same stretches daily for decades, and fishermen who knew each eddy and pool intimately. These riverside sages would have taught him the location of "chutes" (passages where the current ran deep and swift), the significance of "towheads" (small alluvial islands), and how to recognize the subtle surface disturbances that signaled submerged "sawyers"—waterlogged trees anchored to the riverbed that could pierce a canoe hull.

And George would have been an avid student, his life depended on it.

For landlubbers like me, here’s a short glossary of river terms that might come in handy as the epic journey of George and William gets underway.

From Racing Canoes to River Currents

By nearly every measure, George was an experienced and athletic canoeist and yachtsman by the time he dipped his oars into the waters of the Mississippi River System. Years of competitive canoeing with the Cleveland Canoe Club combined with disciplined training on Lake Erie's unpredictable waters had given him the physical foundation – the calloused hands and hardened muscles – needed for the grueling downstream journey ahead.

And a lifetime on the water meant George had also developed the keen observation skills of an experienced Great Lakes yachtsman—reading wind patterns from ripples on distant water, detecting approaching weather systems from subtle cloud formations, and maintaining situational awareness across vast stretches of open water. These abilities had served him well on the vast inland seas where sudden squalls could transform calm waters into life-threatening conditions without warning.

The transition from open-water navigation to river travel, however, demanded a fundamental shift in perspective and technique.

On the Great Lakes, George had learned to navigate by distant landmarks, celestial bodies, and compass bearings across open expanses where dangers typically came from above in the form of weather. The Ohio and Mississippi Rivers presented an inverted challenge—the dangers lurked below and around the water rather than above, with constantly shifting channels, submerged obstacles, and powerful currents that could drive a canoe into disaster with little warning.

Even his paddling technique required adaptation; the rhythmic, power-focused strokes that propelled racing canoes efficiently across lakes needed to be supplemented with subtle steering adjustments, ferrying techniques, and the ability to work with rather than against the river’s flows

How George prepared for these aspects of his journey is unknown, however, as in the case of learning about the unpredictability of the river, it’s likely much of his education came one paddle, and one day, at a time, through hard-taught experience.

The wind became a gale, tumbling the water in a way to remind us of many a mad dash on Lake Erie. As the wave crests broke into spray and tumbled on board, the drops froze at once, covering decks and clothing with a coat of ice.

Little headway could be made, as, notwithstanding the windings and turnings of the river, no lee could be found – the wind was blowing up stream directly in our teeth.

A Chute behind Island No. 8 seemed to offer a possible escape, but it proved a delusion and a snare. Grievously we mourned our unwisdom, as the breeze which had toyed with us in the broad open channel, was a gentle zephyr compared with the howling fury that met us in that shute.

In an hour and a half we had covered a short mile; half a mile further on lay the main river, and we hungered to get into that open water as a starving man hungers for rations, but we had yet another foe to meet and conquer.

The water grew shallow as we proceeded the paddles turned up the mud at the bottom, the keels touched, and we were aground. The water in the chute, ordinarily of much less depth than in the main channel, had been blown out by the heavy wind, thus leaving scarcely enough to float a chip, but uncovering a wide stretch of its muddy bottom on each shore – an impassable barrier. 2 ~ George W. Gardner

The Language of Moving Water

Perhaps the most significant adaptation for George was developing what rivermen call "reading water." Unlike the relatively uniform surface of lakes, rivers present a complex text of surface patterns—V-shaped ripples pointing downstream indicating submerged rocks, smooth "pillows" of water sliding over barely submerged obstacles, boils and swirls marking the edges of deep channels, and the distinctive "horizon line" where water drops over submerged ledges.

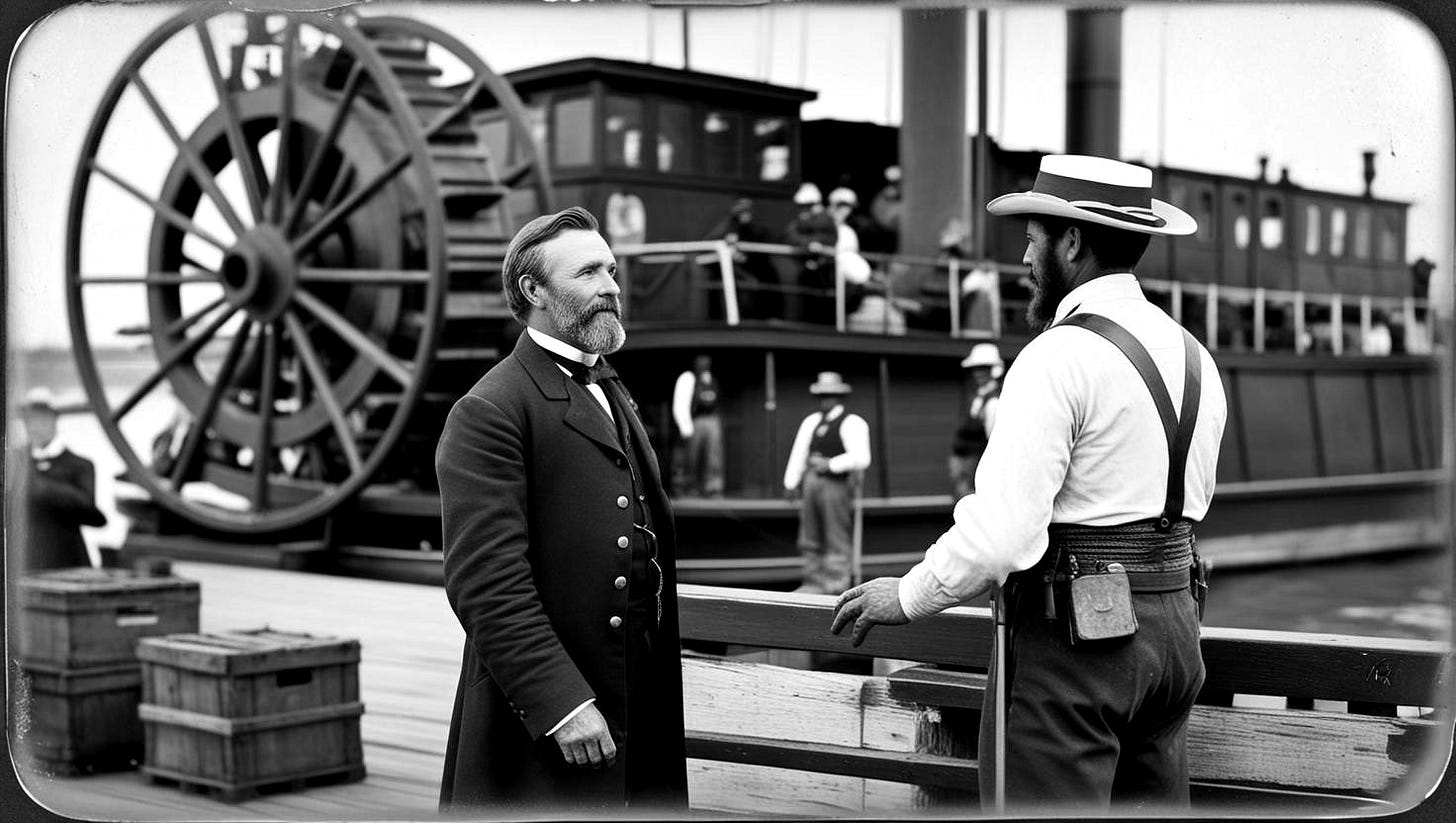

Mark Twain wrote frequently about ”reading the river” in Life on the Mississippi, a skill he’d acquired while working as a 21-year-old apprentice steamboat pilot under the supervision of Captain Horace Bixby. Although just a decade in age separated student from teacher, when it came to the river, Horace was a wisened old-timer of mythical proportion, at least in Twain’s recollection:

'Do you see that long slanting line on the face of the water? Now, that's a reef. Moreover, it's a bluff reef. There is a solid sand-bar under it that is nearly as straight up and down as the side of a house. There is plenty of water close up to it, but mighty little on top of it. If you were to hit it you would knock the boat's brains out. Do you see where the line fringes out at the upper end and begins to fade away?'

'Yes, sir.'

'Well, that is a low place; that is the head of the reef. You can climb over there, and not hurt anything. Cross over, now, and follow along close under the reef—easy water there—not much current.'

I followed the reef along till I approached the fringed end. Then Mr. Bixby said—

'Now get ready. Wait till I give the word. She won't want to mount the reef; a boat hates shoal water. Stand by—wait—WAIT—keep her well in hand. NOW cramp her down! Snatch her! snatch her!'

He seized the other side of the wheel and helped to spin it around until it was hard down, and then we held it so. The boat resisted, and refused to answer for a while, and next she came surging to starboard, mounted the reef, and sent a long, angry ridge of water foaming away from her bows.

'Now watch her; watch her like a cat, or she'll get away from you. When she fights strong and the tiller slips a little, in a jerky, greasy sort of way, let up on her a trifle; it is the way she tells you at night that the water is too shoal; but keep edging her up, little by little, toward the point. You are well up on the bar, now; there is a bar under every point, because the water that comes down around it forms an eddy and allows the sediment to sink.

Do you see those fine lines on the face of the water that branch out like the ribs of a fan. Well, those are little reefs; you want to just miss the ends of them, but run them pretty close.

Now look out—look out! Don't you crowd that slick, greasy-looking place; there ain't nine feet there; she won't stand it. She begins to smell it; look sharp, I tell you! Oh blazes, there you go! Stop the starboard wheel! Quick! Ship up to back! Set her back! 3

Where Skill Meets Survival

All of George’s preparation—from Lake Erie's competitive waters to the knowledge gleaned from Charles Neide —would be tested: The Mississippi demanded respect in a way different from any water he'd known before.

In the coming days and weeks, the river would reveal itself to George not merely as a waterway to be traversed, but as a living entity with moods, temperaments, and stories of its own. Like Twain before him, George would learn to read this "wonderful book" of water, adding his own chapter to the river's long history.

Copyright 2025 Lori Olson White

Have you read the incredible true story of Aimee Henry and Mary Martha Parker? Call Me a Bastard is my longest serialized story to-date, and the one that started it all here on the Lost & Found Story Box. Check out the story from the beginning.

And in case you missed it, here’s a link to my most popular short series to-date, The Incorrigible John George. I hope you’ll agree that “incorrigible” is the best way to describe this old scoundrel!

Please hit the ❤️ button at the bottom of the page to help this story reach more readers. And if you’re not already a subscriber, I’d love to have you join me. Thanks!

The Lost & Found Story Box is reader-supported. When you buy through links on our site, we may earn an affiliate commission.

End Notes

1 Mark Twain, Life on the Mississippi, James R. Osgood & Co., Boston, MA, 1883. Chapter 9.

2 “The Mayor in a Canoe: His Adventures. Between Porkopolis and the Crescent City in Midwinter”, The Cleveland Leader, Cleveland, OH, January 26, 1890, P. 10.

3 Mark Twain, Life on the Mississippi, James R. Osgood & Co., Boston, MA, 1883. Chapter 8.

You've managed to help me recall a terrifying experience with the dreaded river corkscrew. One moment you're floating along in sunshine and rainbows and the next, a submerged curled root deftly flips your canoe upside down into deep water. My daughter and I survived but she was beyond upset for days at the indignity of it all. Great story you're telling!

Geez, Lori! I'm reminded of tow boat pilots in waterways worldwide. Tides combine with varying shallows and massive underwater dangers. You've captured the spirit of every whitewater trip I've ever taken!

Come to think of it, there was that awkward moment the a US aircraft carrier ran aground in San Francisco Bay back in the 1980s. Oops: https://www.19fortyfive.com/2025/04/it-took-6-hours-to-free-a-trapped-u-s-navy-aircraft-carrier-that-ran-aground/