The Epic Canoe Journey of George W. Gardner: PART 9

Contemplation, challenges and the end of a journey

To get the most enjoyment out of this serialized story, please start at the beginning.

Release Date: May 27, 2025

The end of remarkable adventure draws near

As George Gardner and William Eckman put their canoes, The City of Cleveland and The Cuyahoga, back into the muddy waters of the Mississippi River on December 26, 1883, they began the final leg of their journey: New Orleans, their destination, was just 230 miles downriver.

Although the two adventurers had been spending up to ten hours a day on the river, and often traveling 50 miles at a time, they slowed their pace considerably in the coming days, perhaps hoping to extend their journey as long as possible.

It would make sense.

For nearly a month, they’d been simply “George” and “William”, two enthusiastic canoeists sharing the immediate challenges of current and weather, food and shelter. In many ways, the river and the journey had given them new identities, far removed from the ones that awaited them back in Cleveland. Returning home to those other identities – successful businessmen, community leaders, fathers and husbands with responsibilities, expectations and reputations to uphold – may have felt like the tightening of a noose.

Then, too, it’s possible the men were simply experiencing the let-down that comes when the end of a remarkable adventure draws near.

Whatever the reason, George and William traveled just 62 miles in the next two days, spending the first night at Coles Creek Landing on the Mississippi side of the river, and the next in Natchez, MS, a town described in The Western Pilot guidebooks as being “romantically situated on a very high bluff of the east bank of the river”, and having “the appearance of comfort and opulence”

Few details of the next few days are recorded. The log simply states:

With alternating warm and cold weather, we paddled and sailed on, passing out of the cotton belt below Baton Rouge, and into the region of sugar cane. The levees began to impart a new character to the scenery as viewed from the canoes. The planter’s mansions grew more pretentious. Palmetto trees were in view.

George, it seems, had run out of words.

Please hit the ❤️ button at the bottom of the page to help this story reach more readers. And if you’re not already a subscriber, I’d love to have you join me. Thanks!

A vague, dim and shoreless sea

In Life on the Mississippi, Mark Twain describes a scene similar to what George and William likely encountered as they made their journey down the Mississippi from Baton Rouge to New Orleans, well after the sugar crops had been harvested.

The river is more than a mile wide, and very deep—as much as two hundred feet, in places. Both banks, for a good deal over a hundred miles, are shorn of their timber and bordered by continuous sugar plantations, with only here and there a scattering sapling or row of ornamental China-trees. The timber is shorn off clear to the rear of the plantations, from two to four miles.

When the first frost threatens to come, the planters snatch off their crops in a hurry. When they have finished grinding the cane, they form the refuse of the stalks (which they call bagasse) into great piles and set fire to them, though in other sugar countries the bagasse is used for fuel in the furnaces of the sugar mills. Now the piles of damp bagasse burn slowly, and smoke like Satan's own kitchen.

An embankment ten or fifteen feet-high guards both banks of the Mississippi all the way down that lower end of the river, and this embankment is set back from the edge of the shore from ten to perhaps a hundred feet, according to circumstances; say thirty or forty feet, as a general thing. Fill that whole region with an impenetrable gloom of smoke from a hundred miles of burning bagasse piles, when the river is over the banks, and turn a steamboat loose along there at midnight and see how she will feel. And see how you will feel, too!

You find yourself away out in the midst of a vague dim sea that is shoreless, that fades out and loses itself in the murky distances; for you cannot discern the thin rib of embankment, and you are always imagining you see a straggling tree when you don't. The plantations themselves are transformed by the smoke, and look like a part of the sea.

All through your watch you are tortured with the exquisite misery of uncertainty. You hope you are keeping in the river, but you do not know. All that you are sure about is that you are likely to be within six feet of the bank and destruction, when you think you are a good half-mile from shore. And you are sure, also, that if you chance suddenly to fetch up against the embankment and topple your chimneys overboard, you will have the small comfort of knowing that it is about what you were expecting to do. 3

The final pull and some new friends

George and William spent the night of December 30 camped a half a mile above Hard Times Landing, LA, some 91-miles upriver from New Orleans. And, although they realized their journey was approaching a finish, George noted in his log the pair “had made no particular plans for the day.” 4

All that changed, however, when “a sloop-rigged craft carrying an immense log sail and jib” came into sight.

The unusual vessel was known as a lugger, a sturdy, wind-powered boat common on the waters in and around New Orleans, and most often used to transport fresh oysters, though known to haul fruit or vegetables at other times of the year.

An 1881 government report on Louisiana’s oyster industry had this to say about these distinctly Mediterranean boats and their attention-getting sailors:

“The luggers run down the Mississippi generally for about 60 miles, and then through smaller outlets and bayous into Grand Lake bayou and the various grounds on the coast. The men who are employed in this fishery, and also the sailors who own the luggers, are almost altogether Italians and Sicilians, generally of a low order.

Their swarthy faces, long, curly hair, unfamiliar speech, and barbaric love of bright colors in their clothing and about their boats, give a perfectly foreign air to the markets. There is not an American style of rig seen, nor hardly a word of English spoken, in the whole gaily-painted oyster-fleet of Louisiana.” 5

The lugger George and William encountered had just delivered its cargo of fresh fruit, and, now empty, was heading downstream toward New Orleans to collect more.

Perhaps seeking one last adventure, the men from Cleveland paddled closer.

Pulling alongside, we chatted with the master of the craft, one of three constituting the crew. A short parlay and we were aboard. The bronzed sons of Italy were unstinted in their hospitality and refused all compensation thereof. We remained on board sleeping in the hold until eleven o’clock the following morning, embarked in the canoe at Nine-mile Point, and entered upon the final pull. 6

The anticlimactic conclusion to an epic journey

Whether due to travel fatigue, the melancholy of reaching the end of the journey, or something else, George’s final log entry of the trip was both anticlimactic and short on detail:

The air was raw chilly, damp, and uncomfortable. At 1:30 we stepped out of the canoes at the Harbor Police station at the foot of Canal Street, New Orleans – the cruise was finished. 6

The entry, it turned out, mirrored the city’s lack of excitment.

Despite their accomplishment and the many challenges they’d overcome along the way, the arrival of the two Cleveland businessmen into New Orleans went largely unrecognized by the local population, and garnered but a single newspaper notice:

Yesterday afternoon at 2:30 o’clock Mr. George W. Gardner, commodore of the Cleveland Canoe Club, and Mr. J. W. Eckman, of Cuyahoga, secretary of the club, arrived here in their canoes from Cincinnati, and through the kindness of the Harbor police officers housed their boats in the Harbor Station, at the foot of Canal Street.

It was just one year and one week since Dr. Neide and his companions arrived here on Christmas Day, hence the appearance of these gentlemen in their little crafts on the broad bosom of the Father of Waters did not excite an unwanted degree of curiosity. Both gentlemen are pictures of health, and their bronzed cheeks and strong figures are evidence of the benefits of the trip. 7

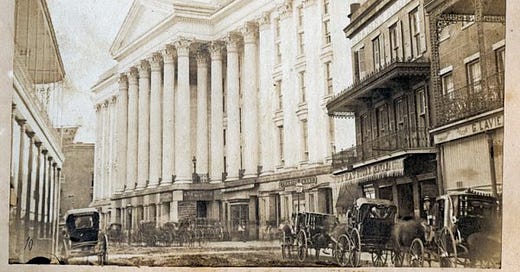

After stowing their canoes, George and William retired to the St. Charles Hotel, the undisputed Queen of New Orleans and a place once called “…the largest, handsomest and most impressive hotel in the world.”

Originally constructed in 1837, the St. Charles which welcomed the two weary travelers at the dawn of 1884 was a near-identical replacement for the original structure which had been destroyed by fire in 1851.

Still, the massive Corinthian columns and Greek-inspired façade of the five-story hotel would have been a welcome change from the tents and cramped canoes to which George and William had become accustomed, and a worthy location for some well-deserved celebrating before the two got back to their real lives.

Although that, curiously, would not happen for more than a month.

The long way home

A week after their arrival in New Orleans, George and William departed for a much-needed vacation, not surprisingly choosing a leisurely cruise to Central America.

Upon their return to the Crescent City some weeks later, the two boarded the steamboat, Guiding Star, once again calling the Mighty Mississippi home as they journeyed north to Louisville.

They got only as far as Evansville, IN, before disaster struck.

“The great Guiding Star came into port about two o’clock this morning [February 2, 1884] with both wheels broken by ice. She will repair here and probably not get off before this morning. Anybody wishing to go up the river will have a royal chance to do so.

The steward, Ed. Brown, assured the Journal folks, soon after arrival, that there would be no famine on the boat so long as he was on board. Jim Paul promises to see everybody safe at Louisville who entrust themselves to his care.

Commander Geo. W. Gardner and W. H. Eckman, of the Cleveland Canoe Club are on board and well taken care of. The party called on the Journal headquarters at 3 o’clock this morning, right side up with care, under the ciceroneship of Fred Gutting, who had taken a contract with Steward Brown not to let the boys suffer for eatables or potables while in town.” 8

It's not known how the rest of their journey went, however, on February 9, the following announcement appeared in the Cleveland Leader:

“Messrs. W. H. Eckman and George W. Gardner returned Thursday evening from a trip through the South, having been gone eleven weeks. They went as far as New Orleans in canoes and then took a steamer for Central America. The rays of the tropic sun caused the faces of both gentlemen to assume a very dark hue.” 9

George and William, it appears, were home at last.

Epilogue

Two years after his epic canoe trip, George W. Gardner went on to become the Mayor of Cleveland and in 1889, he was elected to that position again.

His business ventures continued to expand and thrive, and George remained passionate about yachting, sailing and canoeing for the rest of his life.

Although very little was ever written about the canoe trip he and William took in 1883, there is no lack of record on the path George’s life took afterward or the kind of man he was. 10

“The late Hon. George W. Gardner of Cleveland, combined in his business qualifications and standards of life in rare degree the characteristics which form success in its truest and nest sense. He attained a name and position in the business world which few men of his time and locality were able to acquire. With honor and without animosity he fought his way through the supreme contests of commercial strife in which only the fittest survive. It was his reward to have his. Name placed beyond and above criticism: honorable and straight-forward business conduct assured that. But better, there will ever be connected with his name the remembrance of a record for sterling citizenship and high-minded performance of public service.”

“His business operations, directed by his able and ripe judgement, netted him a handsome fortune and proved the truth of his claim that a man could be thoroughly honorable in his dealings and yet accumulate considerable property, provided he be willing to exert himself and act according to the dictates of his conscience.”

“A leader of men, Mr. Gardner understand human nature and knew how to sway those about him, and, fortunately for the community, his influence always tended toward moral uplift and the betterment of existing conditions.”

George Williams Gardner died December 18, 1911, at the age of 77. He’s buried at Cleveland’s Woodland Cemetery.

Copyright 2025 Lori Olson White

Have you read the incredible true story of Aimee Henry and Mary Martha Parker? Call Me a Bastard is my longest serialized story to-date, and the one that started it all here on the Lost & Found Story Box. Check out the story from the beginning.

And in case you missed it, here’s a link to my most popular short series to-date, The Incorrigible John George. I hope you’ll agree that “incorrigible” is the best way to describe this old scoundrel!

Please hit the ❤️ button at the bottom of the page to help this story reach more readers. And if you’re not already a subscriber, I’d love to have you join me. Thanks!

The Lost & Found Story Box is reader-supported. When you buy through links on our site, we may earn an affiliate commission.

End Notes

1 “The Western Pilot P 113.

2 “The Mayor in a Canoe: His Adventures. Between Porkopolis and the Crescent City in Midwinter”, The Cleveland Leader, Cleveland, OH, January 26, 1890, P. 10.

3 Mark Twain, Life on the Mississippi, James R. Osgood & Co., Boston, MA, 1883. Chapter 11.

4 “The Mayor in a Canoe: His Adventures. Between Porkopolis and the Crescent City in Midwinter”, The Cleveland Leader, Cleveland, OH, January 26, 1890, P. 10.

5 Ernest Ingersoll, “The Oyster Industry: The History and Present Condition of the Fishery Industries, Department of the Interior, Tenth Census of the United States, Francis Walker, President, Washington Government Printing Office, 1881, P. 199.

6 “The Mayor in a Canoe: His Adventures. Between Porkopolis and the Crescent City in Midwinter”, The Cleveland Leader, Cleveland, OH, January 26, 1890, P. 10.

7 “Paddling their own Canoe: Two Gentlemen from Cleveland arrive in their Frail Craft”, The Times-Democrat, New Orleans, LA, January 2, 1884, P. 2.

8 “Late River News”, The Evansville, Journal, Evansville, IN, February 2, 1884, P. 4

9 “Returned from the Tropics”, The Cleveland Leader, Cleveland, OH, February 9, 1884, P. 5.

10 “A History of Cleveland and Its Environs: The Heart of New Connecticut: Vol. II Biography, The Lewis Publishing Company, Chicago and New York, 1918, P. 443-445

Wow, now I want a play by play on that Central American cruise!

It surprised me to learn that they left New Orleans for a trip to Central America. The canoe trip was a fascinating adventure to read about.