Release Date: July 26, 2024

Today when we talk about hysteria, we usually mean some sort of extreme behavior, as in ‘the media's coverage of the event led to a wave of public hysteria.’

But there was a time, not that long ago, when hysertia had a decidedly broader, and perhaps more sinister meaning.

In the early 1900s, hysteria was an actual medical diagnosis, one primarily found in women and believed to be caused by a ‘wandering womb’.

Symptoms of hysteria fell into three broad categories: emotional, physical and behavioral.

Emotional symptoms included things like excessive worry, persistent sadness, hopelessness, a lack of interest in usual activities, rapid mood swings, and crying or laughing a lot. There were, of course, some more serious symptoms such as intrusive thoughts and holding strong beliefs that were clearly false, but those were pretty open to interpretation.

In terms of hysteria’s physical symptoms, they included fainting or dizziness, paralysis or muscle weakness, tremors, numbness or tingling of the hands and feet and persistent tiredness. But also things like indigestion, bloating, trouble falling asleep or staying asleep, frequent headaches, rapid or irregular heartbeats and shortness of breath. And, of course, any and all symptoms or complaints related to a woman’s reproductive system.

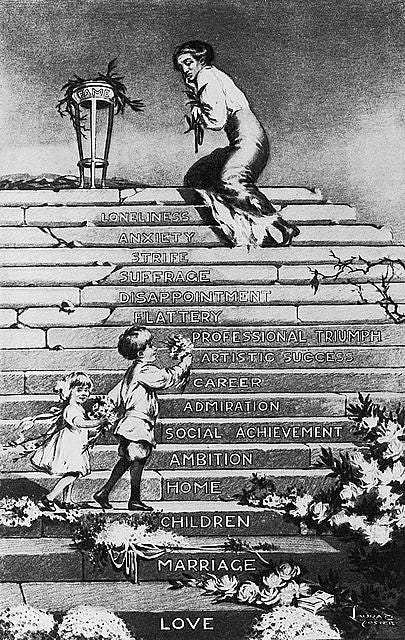

The behavioral symptoms of hysteria, however, were the most interesting. A woman could be diagnoses with hysteria if she:

rejected traditional female roles

was too interested in sex or not interested enough

was too feminine or not feminine enough

pursued higher education or employment

had a desire for independence or autonomy

was creative or imaginative (writers were often hysterical, of course)

became agitated, rebellious or frustrated or even if she was just too talkative.

In other words, women could be labeled mentally ill, subjected to questionable treatments and locked away in asylums for experiencing and expressing the normal emotional and physical ups and downs of being human.

Or even for just wanting more personal freedom.

Political Hysteria

It’s no coincidence that just as the suffrage movement gained momentum in both America and England, both countries experienced what was commonly called an epidemic of hysteria.1

This epidemic was so widespread and specific that the medical establishment even had a name for it, ‘insurgent hysteria’. 2

In 1912, Dr. Leonard Williams, one of the foremost English specialists in mental disease went so far as to declare that “there is no form of pseudo insanity that is not found in the suffragette ranks.”

A New Dance Craze

With so many hysterical women around, the medical community was busy coming up with cures. Some were more unconventional than others, including this cure which was touted in a 1912 edition of the Oakland Enquirer:

“Dancing cures hysteria.” This is the latest mental discovery, made by Dr. Doletti, an Italian physician here, who claims that out of 100 hysterical women for whom he prescribed dancing, 73 were completely cured after dancing three times a week for three months. Repeated observation of a marked decrease in hysteria among women during the winter society season caused him to begin to prescribe the treatment, which he is still continuing with remark able success, says the doctor. “Dreamy waltzes are the most efficacious, “he says, but having never seen the “Grizzly Bear”, “Bunny Hug” or “Turkey Trot”, he refuses to pass upon their merits as a remedy. 3

The Yellow Wallpaper and the Rest Cure

One of the most common, controversial and ultimately written about treatments for hysteria was known as the Rest Cure. Developed by neurologist Dr. Silas Weir Mitchell to treat injured and traumatized Civil War soldiers, the Rest Cure was repurposed and rejigged three decades later to address the hysteria epidemic.

The idea behind it was simple: Hysterics, primarily women but also men, were physically, mentally, emotionally and morally exhausted and overstimulated by their own ambitions and the stress and demands of an ever-changing modern life.

As one treatment center of the day noted, the Rest Cure was needed because:

“…the average American of to-day (sic) lives a life of over-taxation, unrest, worry, and strife. This is true of both men and women, whether in the direction of domestic cares, business enterprises or social ambition. The habit of worry and desire to get ahead of some one else is carried from business and society to the functions of daily life. Everything is done ‘on the rush’ - eating, sleeping, working - even our amusements are carried to the point of dissipation. The strain and pressure of Modern American life often carries on in spite of himself at a pace which can only end in nervous break-down, nervous prostration, and, too often, the asylum, not to speak of the jail.” 4

The only hope of returning to normal life and society was a supervised period of highly structured, rigorously enforced and all-encompassing rest.

Women who underwent the most draconian form of the Rest Cure were confined to bed for weeks or even months at a time, often not even allowed to get up to use the bathroom. They were isolated from all outside stimulation and social contact, and, in the early weeks of treatment at least, not allowed to read, write, knit, converse or interact with anyone other than their doctor or caregiver, both of whom were charged with enforcing absolute physical and moral discipline.

To prevent their muscles from deteriorating, women were subjected to manual stimulation, vigorous massages and electric shock therapy twice daily.

Their diets were initially restricted to three ounces of milk fat every three hours, after which additional non-stimulating foods could slowly be added. And, of course, patients were weighed regularly.

In 1884, a woman by the name of Charlotte Perkins Stetson was sent to Dr. Mitchell after being diagnosed with hysteria. In truth and, with the benefit of modern knowledge about mental health, she was suffering from postpartum depression after the birth of her daughter several months earlier. A writer by trade and heart – she was the great niece of Harriet Beecher Stowe, the author of Uncle Tom’s Cabin – Charlotte went on to fictionalize her experiences with Dr. Mitchell and his Rest Cure in a short story titled, The Yellow Wallpaper.

Published in 1891, The Yellow Wallpaper, immediately became a lightning rod for conversations around the topic of women and mental health, and ultimately led to much-needed awareness and change.

In 1913, by then a famous figure in the women’s movement, Charlotte opened up about why she wrote The Yellow Wallpaper and the impact it had one her in The Forerunner, a monthly magazine she’d founded, funded, controlled and produced.

Many and many a reader has asked that. When the story first came out, in the New England Magazine about 1891, a Boston physician made protest in The Transcript. Such a story ought not to be written, he said; it was enough to drive anyone mad to read it.

Another physician, in Kansas I think, wrote to say that it was the best description of incipient insanity he had ever seen, and–begging my pardon– had I been there?

Now the story of the story is this:

For many years I suffered from a severe and continuous nervous breakdown tending to melancholia–and beyond. During about the third year of this trouble I went, in devout faith and some faint stir of hope, to a noted specialist in nervous diseases, the best known in the country. This wise man put me to bed and applied the rest cure, to which a still-good physique responded so promptly that he concluded there was nothing much the matter with me, and sent me home with solemn advice to “live as domestic a life as far as possible,” to “have but two hours’ intellectual life a day,” and “never to touch pen, brush, or pencil again” as long as I lived. This was in 1887.

I went home and obeyed those directions for some three months, and came so near the borderline of utter mental ruin that I could see over.

Then, using the remnants of intelligence that remained, and helped by a wise friend, I cast the noted specialist’s advice to the winds and went to work again–work, the normal life of every human being; work, in which is joy and growth and service, without which one is a pauper and a para- site–ultimately recovering some measure of power.

Being naturally moved to rejoicing by this narrow escape, I wrote The Yellow Wallpaper, with its embellishments and additions, to carry out the ideal (I never had hallucinations or objections to my mural decorations) and sent a copy to the physician who so nearly drove me mad. He never acknowledged it.

The little book is valued by alienists and as a good specimen of one kind of literature. It has, to my knowledge, saved one woman from a similar fate–so terrifying her family that they let her out into normal activity and she recovered.

But the best result is this. Many years later I was told that the great specialist had admitted to friends of his that he had altered his treatment of neurasthenia since reading The Yellow Wallpaper.

It was not intended to drive people crazy, but to save people from being driven crazy, and it worked.” 5

When I was in college an eon ago, I actually remember reading The Yellow Wallpaper for a class assignment. I was young and didn’t really know much, but remember thinking it was a haunting story.

In researching Aimee Henry and Mary Martha Parker, and especially the way Aimee’s mental health challenges were weaponized against her, I re-read Charlotte’s short story, and let’s just say it hits a whole lot differently this time around. I’m older, of course, but I’ve also been through pregnancy and postpartum, not to mention the hormonal shenanigans of menopause. And I’ve stood beside moms who’ve suffered with postpartum depression and also its sister, postpartum anxiety. The idea that medical professionals thought enforced isolation and deprivation was a good idea during what’s one of the most emotionally vulnerable and raw times in a woman’s life is beyond understanding.

It’s not known exactly what Aimee’s mental health situation was when Mary Martha tried to have her committed to the Butler Asylum in 1912, or if the attempt was really just a convenient way to keep Aimee silent and make her an unreliable source of information in the future.

What is known, however, is that many institutions like Butler had fully embraced Dr. Mitchell’s Rest Cure in some shape or form. Some followed it to the last drop of milk fat, but others simply provided women with a quiet refuge to relax and rebalance. Which might not have been a bad thing. Sometimes we can all use a little solitude, right?

And finally, I don’t want to leave the impression that Dr, Mitchell was a monster or that his work in neurology and mental health wasn’t genuine or foundational or even of value. So, here’s a bit from an 1871 tract he authored titled “Wear and Tear, or Hints for the Overworked”.

Despite being 153 years old, it’s still a good reminder about the differences between wear and tear, and something from which we can all benefit.

“Wear is a natural and legitimate result of lawful use, and it is what we all have to put up with as a result of years of activity of brain and body. Tear is another matter: it comes of hard or evil usage of body or engine, of putting things to wrong purposes, using a chisel for a screw-driver, penknife for a gimlet. Long strain, or the sudden demand of strength from weakness, causes tear. Wear comes of use; tear, of abuse.” 6

Copyright 2024 Lori Olson White

If you or someone you know is experiencing postpartum depression, postpartum anxiety, or just needs someone to talk to, please reach out to the good folks at Post Partum Support International. Their motto says it all:

You are not alone. You are not to blame. With help, you will be well.

US National Crisis Textline: Text HOME to 741741

Call or Text our US HelpLine: Call 1-800-944-4773, Text: 800-944-4773

National (US) Maternal Mental Health Hotline: Call or Text 1-833-852-6262

Call Me A Bastard is a weekly serialized book that tells the true and scandalous story of Aimee Henry and Mary Martha Parker. New chapters are released each Tuesday beginning June 25, 2024. Subscribe today, and we’ll deliver Call Me a Bastard and a bunch of other fantastic free content to your email each week!

If you enjoy bonus content like this, or just want to support The Lost & Found Story Box, we’d love to have you as a paid subscriber. Your paid subscription helps support Call Me a Bastard and future projects and gives you access to exclusive content like Author Q&A Sessions, Guest Features, Fan Engagement Opportunities, Virtual Wrap-up Parties, Unlimited access to the Story Archives and more!

Read Call Me a Bastard from the beginning.

The Lost & Found Story Box is reader-supported. When you buy through links on our site, we may earn an affiliate commission.

Endnotes

1 Miller, Georgianna Oakly (209). The Rhetoric of Hysteria in the U.A., 1830-1930: Suffragists, Sirens, Psychoses [Doctoral dissertation, University of Arizona].

2 “It’s Insurgent Hysteria: English Specialist Says That’s the Ailment of Suffragettes”, The Sun, New York, NY, April 7, 1912, P.1.

3 “Dreamy Waltz will Cure Hysteria, is Opinion of Noted Italian Specialist”, Oakland Enquirer, Oakland, CA, March 19, 1912, P. 1.

4 Rest cures: The Narrative Life of a by Michael Robert Blackie

5 Charlotte Perkins Gilman, “Why I Wrote The Yellow Wallpaper”, The Forerunner: A Monthly Magazine by Charlotte Perkins Gilman, Vol. IV, No. 10, October, 1913, New York, NY, p. 271

6 A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the graduate School University of Southern California In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philiosophy (English) May 2006.

When I started reading this my mind immediately went to JFK's sister, Rosemary. Who at the age of 23 , her family allowed a surgeon to do a lobotomy on her to change her behavior. Rather drastic and it ruined her life.

Really interesting to read Lori. The Yellow Wallpaper is such an interesting piece of work when looking at hysteria. I first read it for my degree about 25 years ago and it stayed with me. I immediately drew on it for my book and own post on Substack. Thanks again for this post