To get the most enjoyment out of this serialized story, please start at the beginning.

Release Date: May 13, 2025

A first glimpse of the Mississippi

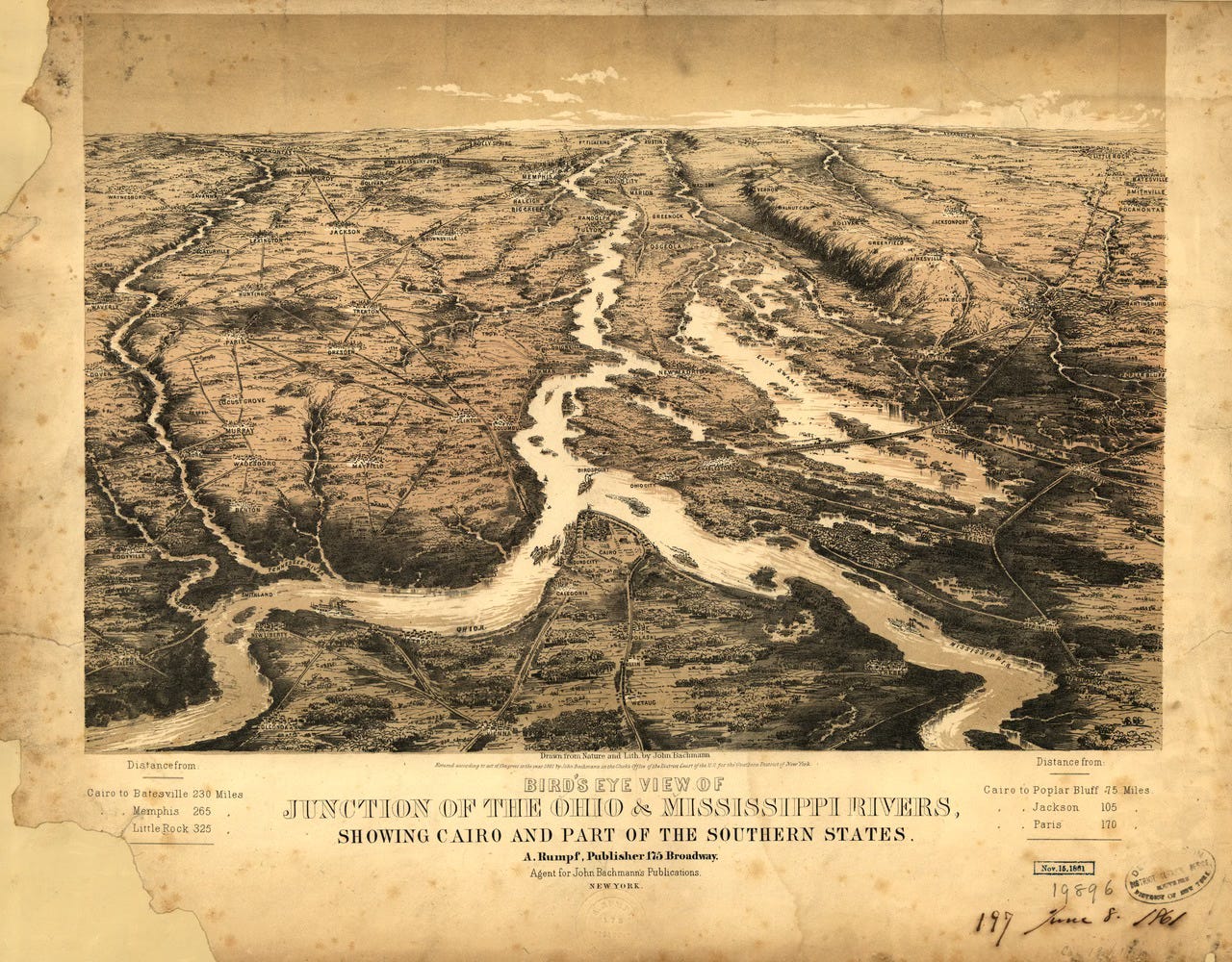

The excitement of their encounter with Captain Luty behind them, George and William turned toward their next milestone, entrance into the Mighty Mississippi River near Cairo, IL.

The landscape was changing—the hills of the upper Ohio giving way to flatter terrain as they approached the confluence with the Mississippi.

The dense woodlands becoming open spaces occupied, not by oaks and hickories, but by wetlands and vast, flat expands.

And the river itself was widening, making it nearly impossible for the two canoeists to travel together.

It was, George noted, the nearest approach to the lonesome feeling during the cruise. 1

But it wasn’t just the landscape that was changing.

Winter weather was settling into the river valley, as well, with temperatures dropping into the 30s and 40s at night, and reaching only into the 50s during the day. When the warmer river water met the colder air, dense fog banks developed which made navigation on the ever-widening river even more treacherous.

On December 13, 1883, three weeks to the day after they’d entered the Ohio River in Cincinnati, George and William paddled into Cairo, IL and got their first glimpse of the Mighty Mississippi River.

Not, however, at the same time, at least according to the local papers:

At 6 o’clock last night (December 13) Mayor Geo. W. Gardner of Cleveland, Ohio, arrived here and put up at the Halliday. He came in a beautiful little canoe in which he padded all by himself all the way down the river from Cincinnati, which port he left on Thanksgiving Day. He was accompanied by a friend, Mr. W. H. Eckman, in another canoe of like perfection, but the latter got a little behind and did not reach here last night. It was supposed that he stopped at Mound City, IL. 2

Their journey had already taken George and William some 538 miles across five states.

Three more states and 1,111 miles lay ahead.

Please hit the ❤️ button at the bottom of the page to help this story reach more readers. And if you’re not already a subscriber, I’d love to have you join me. Thanks!

A winter storm cometh

After spending a few days in Cairo, perhaps celebrating the milestone they’d just met, the gentlemen from Cleveland resumed their journey, choosing to take advantage of the favorable morning breeze by hoisting their sails instead of paddling.

For three hours the breeze held favorable, and had it not been for the frosty leaven in the wind, the run would have been most enjoyable. At the end of that time, a twist in the waterway and another in the wind gave us such work as fully contracted the cold. The wind increased and set in dead ahead, a nasty, wet, choppy sea resulted.

After the noon hour the mercury had fallen several degrees, the spray froze as it fell upon deck, and paddling became labor.

By the time George and William stopped for the night in Hickman, KY, a major agricultural port of the day, the temperature was 32 F.

And, like them, it was heading south. 3

The Triple Trap: No Forward, No Back, No Camp

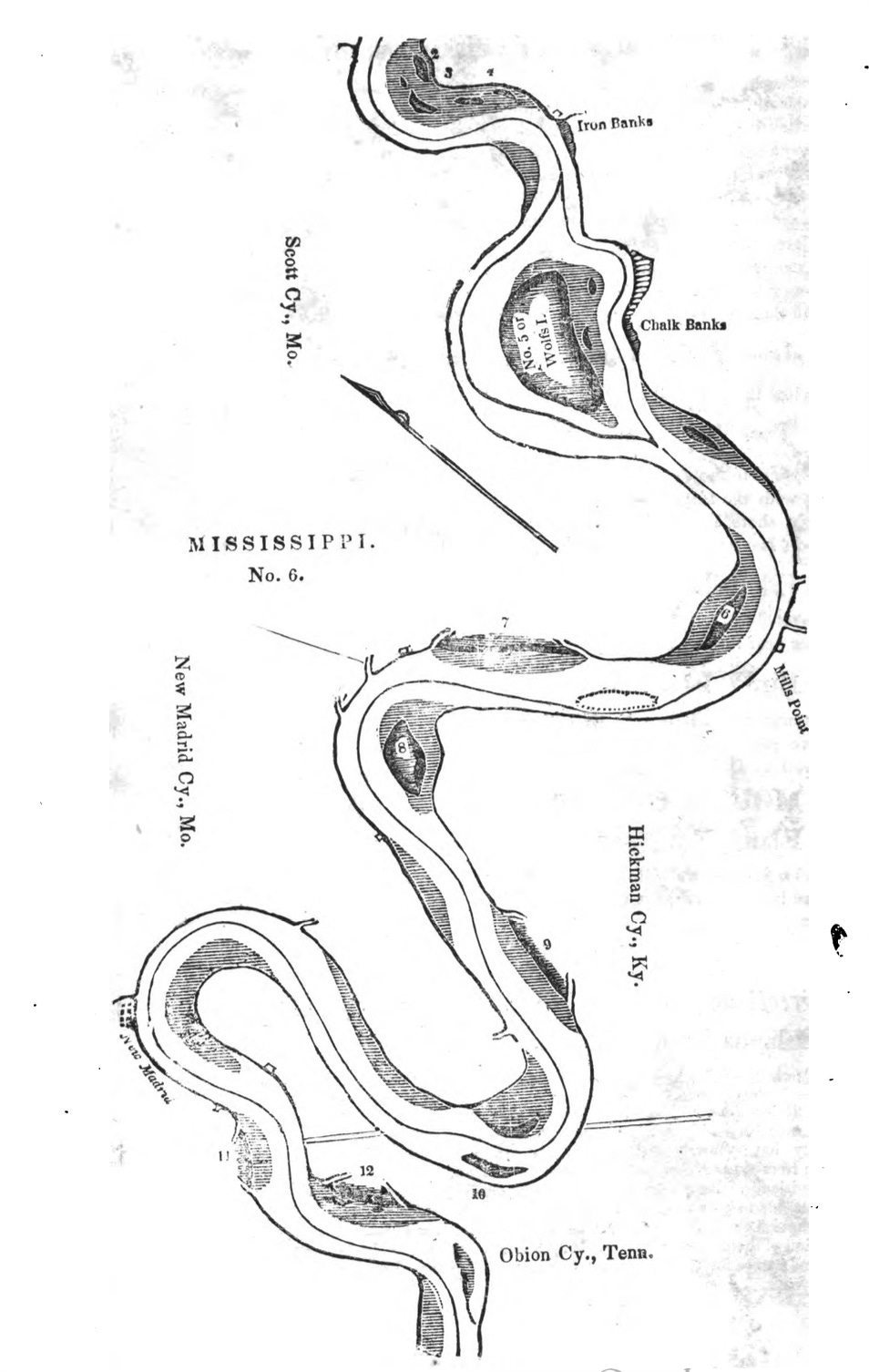

The next morning, George and William set their sights on what they called Camp Neide, a bend in the Mississippi just past Island No. 10, where their friend and fellow canoe enthusiast, Dr. Charles Neide, had been stranded for three days during a winter storm just a year earlier.

Not that George and William wanted, or even expected, to recreate Charles’ experience. No, their desire to spend the night at Camp Neide was more of a nod to their friend, a common bond and story they could share back on dry land.

Mother Nature, however, had other plans.

What started out as a cool breeze as they left Hickman, quickly grew into a relentless headwind, making it difficult for the two adventurers to make any forward movement in their vessels, the City of Cleveland and the Cuyahoga. And with each turn of the river, the wind would shift again, pushing the canoes out of the channel and up against the many sand bars, snags and other obstacles that hugged shore.

As they neared Island No. 8 – named because it was the eighth island on the Mississippi, but which was, coincidentally, also located eight miles beyond Hickman – George and William shouted directions over the howling wind. The guidebooks had suggested they keep down the left shore on approach, then angle out into the middle of the river, passing the island on the right. But the maps had shown a chute, a possible shortcut, which might get them out of the wind for a while.

Exhausted and cold, their butternut duck outfits covered in thickening ice, George and William decided to take a chance.

It was a decision they instantly regretted.

As the wind rushed through the narrow natural gorge between the island and the shore, the two canoeists unknowingly entered what could only be described as a wind tunnel. The winds howled, driving bitter waves over the decks of their canoes and thwarting every effort George and William made to maneuver their crafts.

But the wind wasn’t only pushing around the canoes, it was also pushing the churning water out of the chute. With each attempt to paddle, the men dug deeper and deeper into the river’s notoriously muddy bottom. Movement became impossible. The chute they’d hoped would provide a shortcut, instead became a trap.

To land and go into camp was thus made impossible; to go ahead picking out a channel as we proceeded involved drudgery, and a fair chance of being defeated in the end; to retrace our steps, go back over that water we had struggled so to master –the situation was interesting.

The storm of wind continued with unabated fury rendering the progress slow and paddling wearisome. Finally a high headland, jutting well out into the stream, indicating a sharp bend in the river, loomed up ahead, below that bluff lay Everett farm and the end of our day's toil. The spruce blades were plied with renewed vigor and the headland gained.

A tangled mass of driftwood had lodged on the narrow shelf of mud and sand at the upper base of the bluff. This had, from time to time, been added to as logs and trees which had been uprooted and brought down by the floods, were caught on their way and held by the entangled mass, through which the current rushed and with an angry hiss that warned us against too there an approach. Beyond this barrier, swaying and twisting and groaning under the lash of wind and current, was the open river.

Catching our breath under the lee of the headland, and adjusting seats, paddles, and belongings for the impending struggle, we pulled straight out into the stream, the wind carrying the canoes several points upstream as they came broadside to. Then came a tug. In a few minutes the conviction was borne in upon our inner consciousness that the hour of defeat had come.

That bend was our Waterloo. Twice we essayed it. Already the shades of evening were upon us, the sky was crowded with heavy masses of flying storm clouds; in another hour deep, dense darkness would prevail.

We were entirely ignorant of the formation of the banks below, and at the best speed we might attain it would require more than an hour to get through that howling gorge.

Wearily and silently we pulled for shore and began the search for a camping ground. After a long and discouraging hunt we could do no better than pitch the tent on the narrow border or shelf of drift encumbered sand at the base of the bluff. The bluff presented a perpendicular wall over thirty feet high, the top being, so far as we could discover, entirely inaccessible from our camp. The sand shelf was scarcely ten feet wide and at no place over six inches above the water.

Thus hemmed in with an unscalable wall back of us and a treacherous flood in front, liable at any hour to fall or rise indefinitely, the situation and outlook for a sound and enjoyable sleep were like discouraging.

Stiff and numb with the cold and the unusually severe strain upon muscle and patience, covered with mud and ice as we were, the unpacking and pitching of the tent and preparations for the night went forward slowly.

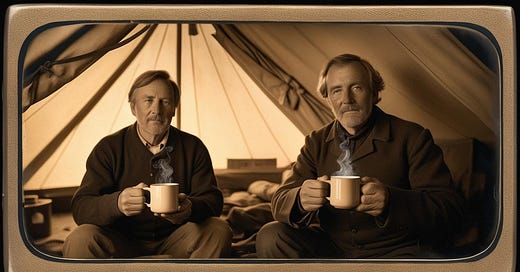

It was 9 o’clock before the supper, prepared over the spirits stove inside the tent, was dispatched. As I recall it, the conversation was neither extended nor animated. Something like this:

“Say, Bill, make it a little stronger and hotter.”

“Can't do, Commodore, it was clear stuff and boiling.”

Then we sank to rest with the mercury at the freezing point. This was Camp Neide, located behind Island No. 10, of war fame, and seven miles above New Madrid, Kentucky. 4

An unexpected holiday from paddling

When the sun rose the next day, the temperatures were still frigid, but the howling wind had died down to a workable breeze. After a breakfast of chicken soup, fried bacon, hardtack and coffee, George and William were off, once again taking advantage of the wind to power their crafts through the tight channels and bends of this stretch of the Mississippi.

Then disaster struck.

Scarcely had we got underway, however, when the ring of the skipper's mainsail snapped and the canvas went overboard; the damage was beyond repair and, to remedy as far as possible of the disaster, the two canoes were again lashed together and the bulging sails of the Cuyahoga carried the twin craft over the waters booming.

Sailing thus, we passed New Madrid without stopping, simply answering the greetings of the several knots of citizens on shore by long blasts of our horns. The wind died away and the paddles were resumed.

It grew colder as the day advanced, and paddling was largely more conductive to comfort than sailing, if anything approaching comfort could be said to exist in such an atmosphere. 5

Some two miles below New Madrid, George and William came up on a small south-bound stern-wheel steamboat, the Richmond. They pulled alongside and, after brief introductions, the captain invited the two weary travelers aboard.

For the next five days, George and William watched the world go by in leisure, “toasting their shins before a hot stove in the cabin”.

It was their longest holiday from paddling of the journey, and one that came to an end on the evening before Christmas Eve in Vicksburg, MS, some 528 miles south of where it had begun.

Copyright 2025 Lori Olson White

Have you read the incredible true story of Aimee Henry and Mary Martha Parker? Call Me a Bastard is my longest serialized story to-date, and the one that started it all here on the Lost & Found Story Box. Check out the story from the beginning.

And in case you missed it, here’s a link to my most popular short series to-date, The Incorrigible John George. I hope you’ll agree that “incorrigible” is the best way to describe this old scoundrel!

Please hit the ❤️ button at the bottom of the page to help this story reach more readers. And if you’re not already a subscriber, I’d love to have you join me. Thanks!

The Lost & Found Story Box is reader-supported. When you buy through links on our site, we may earn an affiliate commission.

End Notes

1 “Daily Bulletin”, The Cairo Bulletin, Cairo, IL, December 14, 1883, P. 4.

2 -5 “The Mayor in a Canoe: His Adventures. Between Porkopolis and the Crescent City in Midwinter”, The Cleveland Leader, Cleveland, OH, January 26, 1890, P. 10.

If I recall correctly, there was a concern about too much white water in the spring, which may have delayed their departure, but it still surprised me where they were in December.

What an adventure! I am pleased they found a little respite aboard the Richmond before continuing on.